April 15, 2014 // Local

Rwandan genocide survivors find hope in faith community

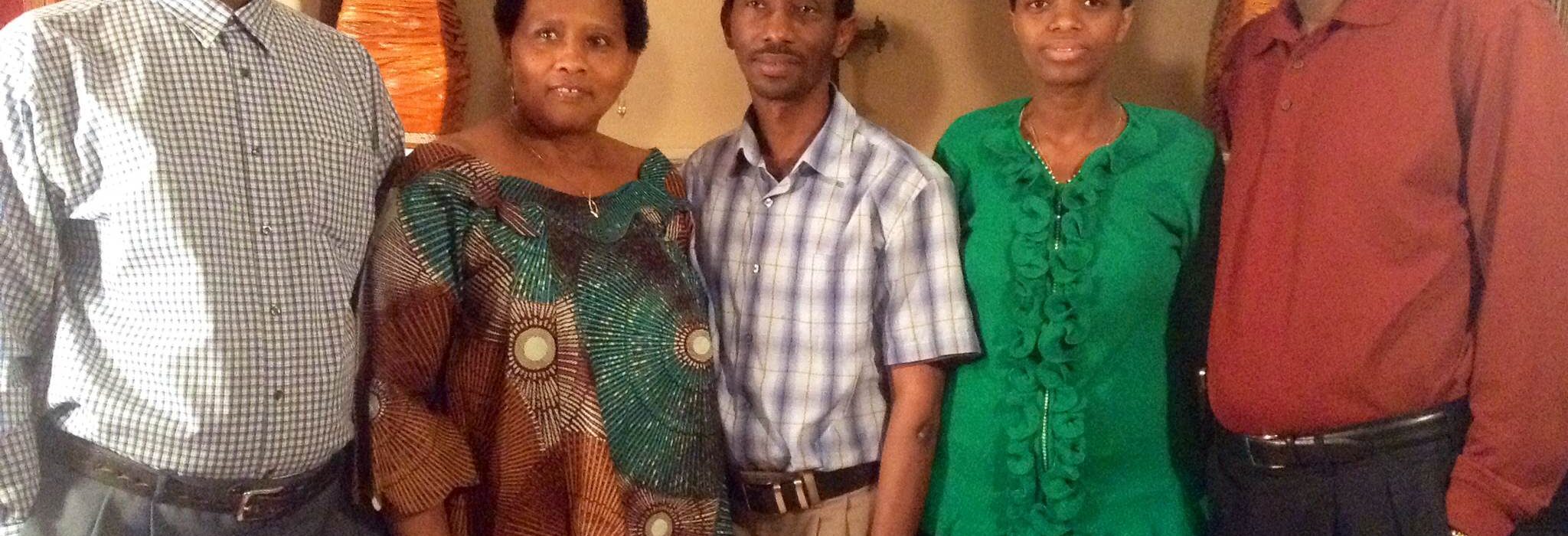

Survivors of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, who now reside in the local Michiana area are, from left, Faustin Semuhungu, Immaculee Mukantaganira, Jean Claude Mugenzi, Catherine Mutuyimana, and Gaetan Gatete.

By Allison Ciraulo

SOUTH BEND — In Eastertide of 1994, within the space of 100 days, nearly 1 million Rwandans were murdered in a conflict that the world would recognize too late as genocide.

The victims were primarily Tutsis, an ethnic minority in Rwanda who had been subjected to ongoing discrimination and violence since national independence from Belgium in 1962. Extremist militias of the dominant Hutu ethnic group were responsible for carrying out the strategically planned genocide, assisted by the Hutu Power government, local officials and ordinary citizens.

About 300,000 Tutsis survived the killing spree that came to an end in July 1994. Betrayed by their own neighbors and forced to watch their family members slaughtered in front of them, they were left to pick up the pieces of their lives and attempt to move forward.

Around 2 million Hutus, both perpetrators and innocent moderates, also were displaced following the genocide, fleeing to neighboring countries to escape retribution.

Many Rwandan refugees came to the U.S. in the years following the genocide. Currently, about 300 survivors of the genocide live in Michiana and the greater Chicago area, and in 2012 they established the Rwandan American Community of the Midwest. They have built new lives in the U.S., but the burden these survivors carry remains heavy even 20 years after the genocide.

Jean Claude Mugenzi was 24 years old when the genocide began. He remembers laying on the ground as each member of his family was shot. He sustained a gunshot wound to the arm, but was able to escape with the help of the rebels, a group known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front that eventually wrested power from the Hutu government.

Mugenzi secured a job with the United Nations in Rwanda in September 1994. Though he made $300 a month, a lot of money then, he quickly realized that no salary could compensate for his loss.

“I remember that I was very sad, telling myself, ‘What’s the point of having money when I no longer have my family?’ Life had lost meaning somehow,” he says.

Mugenzi subsequently worked for several humanitarian and peace-building organizations in Rwanda and began to make documentaries about the genocide as a part of his own healing process.

“Being a filmmaker gave me an opportunity to be at the service of those who could not tell their story otherwise, and this gave me a reason to go on,” he says.

Immaculee Mukantaganira lost her husband and two children in the genocide. It was by “a miracle of God” that she survived, she says.

Two decades later, she has established a new life in the U.S., but the trauma of what she lived through still haunts her.

“It’s just something that will not go away,” she confirms.

After the genocide, she stopped going to church for a time, despite having been raised in a devout Catholic family. She says that she couldn’t understand how God could allow a million people to die, especially her family members who had served Him so faithfully.

Catherine Mutuyimana struggled similarly with her faith after the genocide. “You would go to church and the killers would be there,” she recalls. Mutuyimana saw her parents murdered by machete in a mass killing where she was spared only because she lay undetected under the bodies of slain Tutsis.

One of the chilling ironies of the Rwandan genocide is that the perpetrators and the victims of the murders were often friends and neighbors. They were the people “with whom we’d shared everything, who came to our parties,” says Mugenzi.

They were also their fellow parishioners, both Catholics and Protestants who had fallen captive to the extremist media’s call for a “final solution” to the Tutsi problem.

In 1994, about 90 percent of Rwandans were Christian, but “the tribe was more powerful than the Church,” says Faustin Semuhungu.

Semuhungu came to the United States in 1988 on a student visa as the social situation for Tutsis in Rwanda was deteriorating. He was living with friends in Dowagiac, Mich., when he received the news. One of 15 children, Semuhungu’s parents and all seven siblings living in Rwanda at the time were killed by Hutu militias.

Despite the initial struggle to return to the Church, the survivors of the Rwandan genocide have found healing and hope in their faith.

“I came to realize that God is our comfort. There’s no way we can live without Him,” says Mukantaganira. Part of her healing process included organizing a Mass of thanksgiving for her deceased family members.

As immigrants to the U.S., the survivors depend upon one another and their local parishes for emotional and spiritual nourishment, and to stand in for the family and friends they lost in the genocide.

The Rwandan American Community has planned a commemoration of the genocide to be held on April 26, with the theme “Remember — Unite — Renew.”

The commemoration will include a keynote address by Dr. James Waller, chair of Holocaust Studies at Keene State College, who has conducted research on the psychology of genocide. A panel discussion and a survivor testimony will follow, and the event will conclude with an audio-visual presentation honoring those who lost their lives in the genocide.

Gaetan Gatete, president of the executive committee for the Rwandan American Community, feels that the commemoration is an opportunity for the Christian community to deepen their faith and practice solidarity through listening to the stories of the survivors.

The focus of the commemoration, the survivors say, could be summed up by the word “komera,” a term in Kinyarwanda, the official language of Rwanda, meaning “be strong; we’re with you.”

The Rwandan American Community is made up of men and women who come from both Hutu and Tutsi backgrounds, but they have left behind the ethnic identities that brought about the atrocities of 1994. The survivors live side-by-side and bear the lingering wounds of genocide together.

“We would like the people of God to come and support us,” Mukantaganira says, “to hear our stories, to see those faded photos of the people we lost, to sit with us and cry with us, hug us or smile at us. To heal, we need support.”

The 20th Commemoration of the Genocide Against the Tutsi will be held from 2:30-6 p.m. on April 26, at McKenna Hall on the campus of the University of Notre Dame, 130 Notre Dame Ave. The event is open to the public. For more information, contact Immaculee Mukantaganira at [email protected].

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.