December 6, 2023 // Diocese

From French Persecution to a New Eden: Early Catholicism in Indiana

By Alex Krouse

In 1818, Father Simon Brute, a leading Catholic missionary in Indiana, stated, “The Age of Reason, as [Thomas] Paine calls it, was, as they hoped, fully established in our France. … Now, it all seems like a dream. … Those who had established them supposed that they would accustom the multitude without religion.” Father Brute was referencing the rise of Revolutionary France that began with Enlightenment ideals but ended with persecution of the Catholic Church and a movement to de-Christianize society. It was in this tragic history that Father Brute grew up in the Catholic faith along with other pioneer missionaries who spread Catholicism in Indiana.

Brute was born in Rennes, France, in 1779. A historic city with roots thousands of years old, Rennes had an established Catholic presence by A.D. 453 that continued for at least another 1,000 years. Yet, when Brute was in school in the early 1790s, he saw dramatic changes occurring in France. The once-Catholic monarchy quickly transitioned into turmoil with the advent of the French Revolution, which was driven by several factors, including widespread economic hardship and an animosity toward the dependence of the Catholic Church and nobility.

Brute witnessed steps taken by revolutionaries to shake the foundation of Catholicism that was entrenched deep within the people, the country, and the culture. The government of France began to implement

laws to curtail Church influence. One such law required all clergy to profess an oath to France as having authority over all religious matters, which was viewed as loyalty of country over God. Brute recalled, “As soon as it became a law, the most violent measures were taken to oblige the bishops and clergy to take it.” For example, according to an eyewitness, a priest was approached after Mass by thousands “demanding him to take the oath” or face the “pain of being dragged out of the pulpit.”

The focus of proclaiming authority in France over God was met with resistance by the Church and clergy, but this was just the beginning of what turned into much more violent steps. In the early 1790s, the monarchy was abolished, King Louis XVI was executed, and the tone of the revolution became measurably darker. Brute witnessed two priests he knew get executed – the order of which came from a tribunal led by an old friend of theirs. One of the priests, soon to be under the guillotine, reproached this former friend “and the whole cause he served with their crimes, and remind[ed] him of the Tribunal of an outraged God, before which he would one day have to appear.” Still, the leader called upon guards to silence the priest with the guillotine and ordered four additional priests be beheaded that same day.

Regarding this revolution in France, Charles Dickens wrote in “A Tale of Two Cities,” “Liberty, equality, fraternity, or death – the last, much the easiest to bestow” was commonplace. Despite violent efforts to silence the Church, though, whispers of Catholicism and Christianity somehow managed to survive. The destructive work to remove Christian roots from France would require more than changed laws and increased violence. According to revolutionaries, it needed a complete ideological shift among the populace.

A national motto for France was created to capture a new ideology: “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” This motto was credited to Antoine-Francois Momoro and Maximilien Robespierre. They understood that requiring allegiance through laws and silencing the most vocal opponents with violence was not enough. Therefore, Momoro, one of the most anti-religion revolutionaries, developed a replacement for Christianity. Famous French writer Voltaire once said, “If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him,” and that was precisely Momoro’s solution. The Cult of Reason became France’s first state-sponsored substitute for Christianity. As Brute noted, “I can still see with my mind’s eye the curious processions which they made through the streets of the city on those days, going to the Temple of Reason.”

This “religion” sought to deify core principles of reason, liberty, nature, and others. It culminated in the Festival of Reason at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, where the altar was dismantled and replaced with an altar to “liberty.” Women and girls were clothed in white Roman dresses, and flames were lit, portraying the symbol of Truth. Across all of France, religious statues, crosses, and monuments were desecrated or destroyed.

Momoro’s religion was short-lived, and soon he was under the guillotine himself. Taking its place was the Cult of the Supreme Being led by Robespierre. While this ideology recognized a god, it was vehemently anti-Catholic. Within two months, though, Robespierre also met his death. Still, the persecution of Christians and clergy continued until the end of the century, displacing as many as 30 thousand priests, many of whom were silenced by execution.

This French history provides the backdrop to Brute’s eventual turn to the priesthood. Brute recalled his feelings as “generally a mixture of horror, and pity, and admiration, and exaltation religious views of heaven, mixed with a detestation of deism and naturalism, which at such moments seemed destined to prevail over the Christian religion in France.” Despite Brute’s initial training in medicine, a seminary reopened by 1803, and the calling to become a member of the clergy was evident.

Brute was ordained a priest in 1808 with a strong interest in missionary work. Perhaps his outreach to imprisoned clergy in the early 1790s influenced this. He explained, “I visited them twice while they were confined there, disguised as a baker’s boy, a big bread basket on my head.” The individuals he visited were locked in a church that had been converted to a prison during the French Revolution.

Shortly into his priesthood, Father Brute would be called upon to travel west to the fledgling United States of America. Father Brute spent most of his time in the United States at Mount St. Mary’s College in Maryland. It was there he met Elizabeth Ann Seton, and the two developed a close friendship. At Seton’s death, one of her personal bibles was given to Father Brute and is currently housed in Evansville.

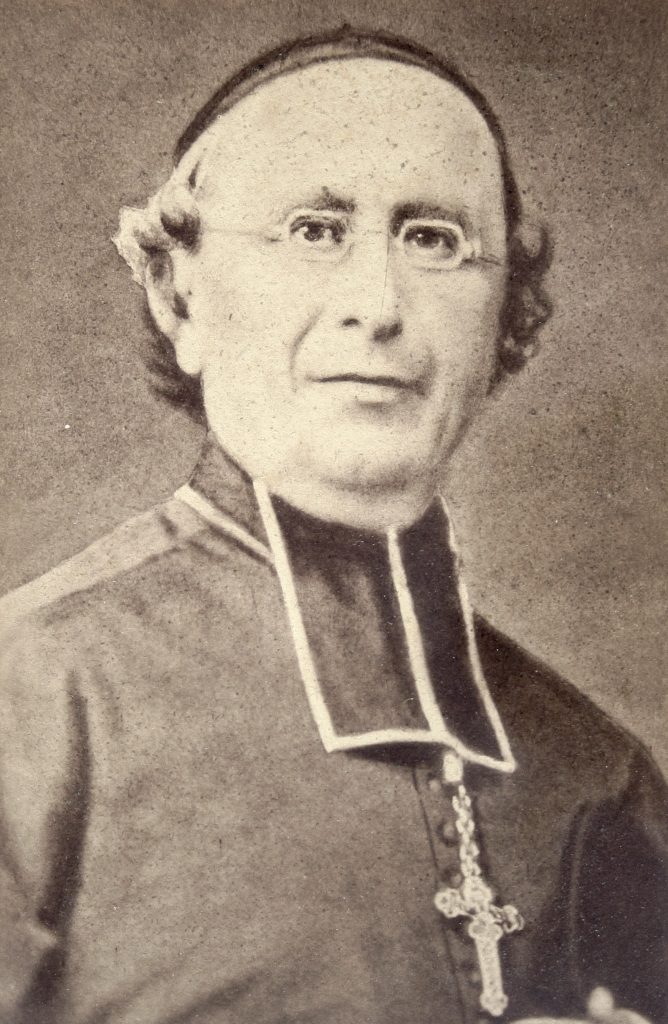

As the United States expanded, so did the need for Catholicism. Father Brute found himself in Indiana and was appointed bishop of Vincennes. In the 1830s, Indiana contained a few hundred thousand individuals, but the populace was scattered. Because of this, it was common for religious missionaries to ride on horseback from town to town to spread Catholicism. However, Bishop Brute needed more priests to spread the word, which required him to visit his native France in search of priests interested in missionary work. Conversations along the route from Rennes to Le Mans sowed French-Catholic ties to Indiana.

On Bishop Brute’s initial trip back to France, he recruited Father Célestin Guynemer de la Hailandière, his future successor. Father de la Hailandière, also born during the French Revolution, was baptized by a priest hiding in his father’s home in revolutionary France. Both Bishop Brute and Father de la Hailandière immediately recruited others to join them in Indiana.

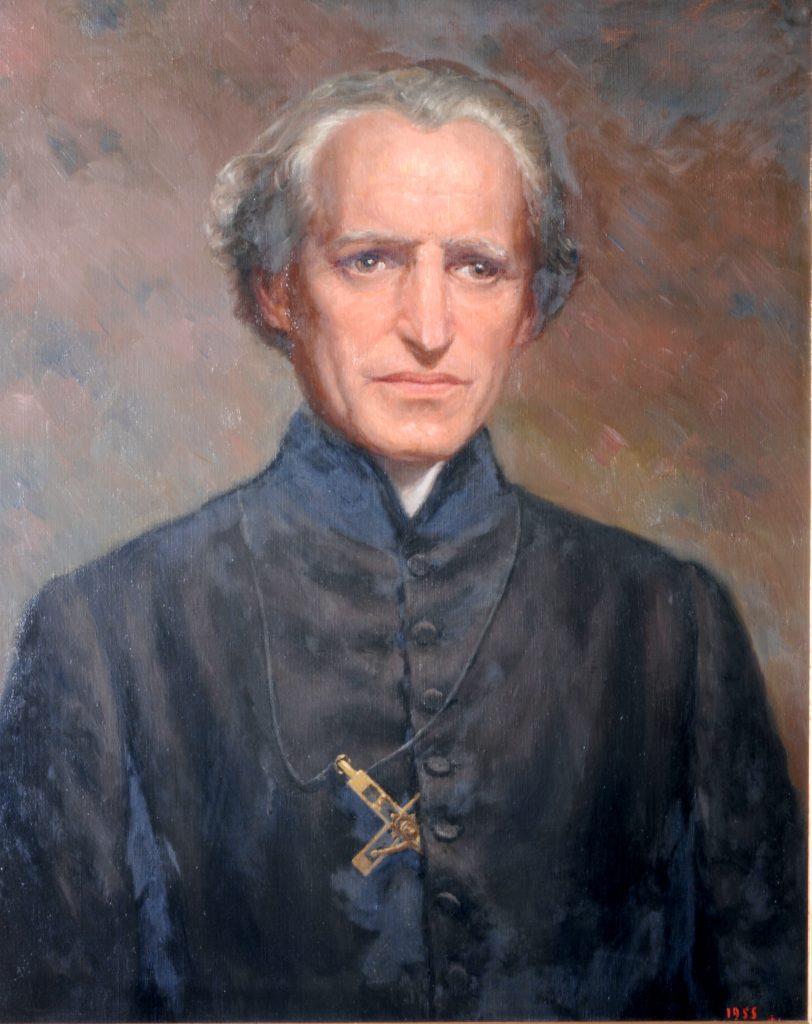

Father Edward Sorin was also one of the first individuals to help lead the missionary expedition. At the time, Father Sorin helped lead the Congregation of Holy Cross with founder Father Basil Anthony Moreau in Le Mans, France. In witnessing Bishop Brute’s efforts, and at the behest of Father de la Hailandière, Father Sorin and the congregation’s six brothers joined them in Indiana in 1841.

Although Father Moreau stayed in France, he was Father Sorin’s mentor and undoubtedly impacted his worldview. Father Moreau, like Bishop Brute, was born during the turmoil in France. His parents, devout Catholics, assisted with the underground Church during that time. Father Moreau spent his initial years rebuilding the Church where as many as two-thirds of the clergy had been exiled or killed.

Father Sorin, who founded the University of Notre Dame, wrote a letter to Father Moreau about the site of the future university. He stated, “Oh, may this new Eden be ever the home of innocence and virtue!” Father Sorin also invited four sisters of the Holy Cross from Le Mans to join him, writing, “Once the sisters arrive, and their presence is ardently desired, they must be prepared not merely to look after the laundry and the infirmary, but also to conduct a school, perhaps even a boarding school.” By 1844, these sisters established the school that would become Saint Mary’s College.

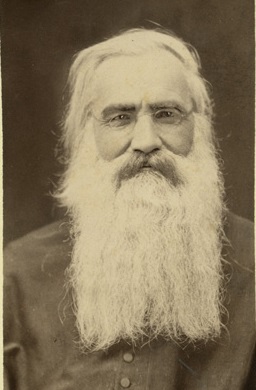

Beyond Father Sorin, Bishop Brute recruited Father Julian Benoit during his 1835 trip to France. Father Benoit came to Indiana in 1840 from Lyons, France. Father Benoit was instrumental in developing the Catholic community around Fort Wayne, helping build the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and cementing Catholic education with St. Mother Theodore Guérin.

Thanks to the monumental efforts of Bishop Brute and these missionaries who forged a path of faith in uncertain times, Catholicism was spread throughout the Diocese Fort Wayne, which was officially established in 1857, and across the midwestern United States. The vast persecution of religion and the Church witnessed by these founding Catholic missionaries in France surely fueled their work to build a “new Eden” in this far-off place.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.