November 15, 2019 // Vatican

Vatican I’s 150th anniversary: Understanding the council yesterday and today

By Kristin Colberg

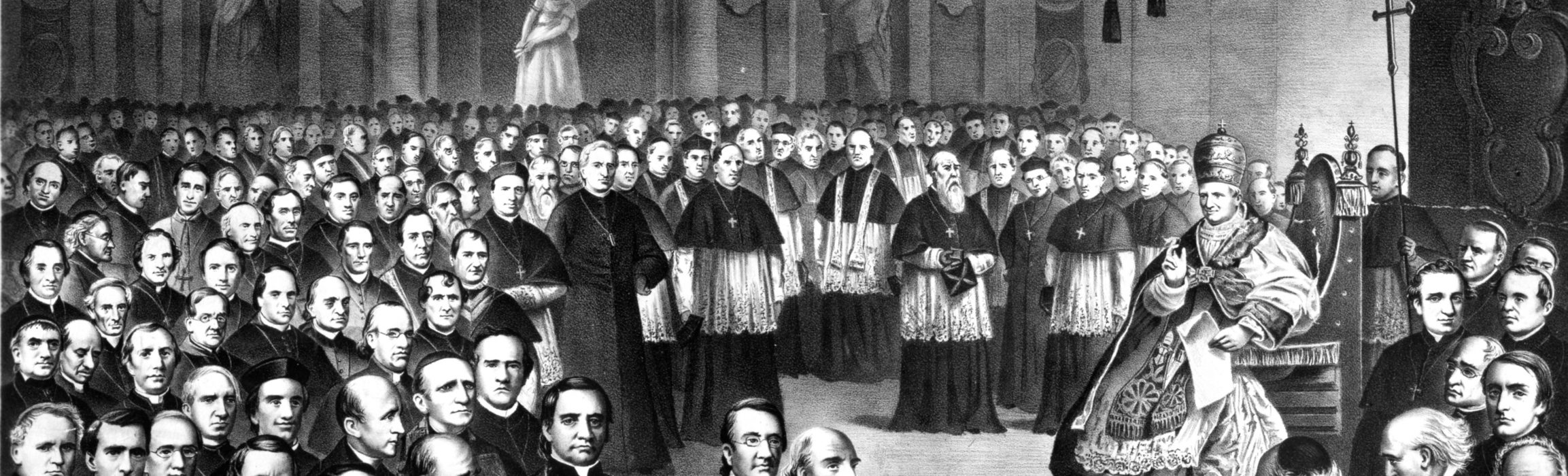

Dec. 8 will mark the 150th anniversary of the opening of the First Vatican Council. On Dec. 8, 1869, more than 700 bishops gathered in St. Peter’s for the 20th ecumenical council and, most famously, defined the doctrine of papal infallibility.

Though the council engaged topics that remain highly relevant, it is often overlooked due to a sense that its teachings are out of step with contemporary views. Frequently, the faithful and scholars alike disregard Vatican I in favor of its successor, Vatican II.

This preference reveals itself by the fact that a Google search for “Vatican I history” can yield the question, “Did you mean Vatican II history?” Despite a general neglect of Vatican I, a renewed engagement with the council in its sesquicentennial year promises to advance many enduring questions for today’s Church.

As with any council, appreciating the historical backdrop of Vatican I is important. The council unfolded during a time of intellectual and political upheaval. Many of the structures and institutions that had long brought order to European society were diminished in the aftershocks of the French Revolution.

The revolution’s wake brought the rise of rationalism, atheism and relativism; these developments, coupled with growing aggressions by secular authorities, set Rome in an extremely defensive posture. Pope Pius IX gathered the bishops hoping that a united Church could address these challenges.

Dec. 8, 2019, will mark the 150th anniversary of the opening of the First Vatican Council. On Dec. 8, 1869, over 700 bishops gathered in St. Peter’s for the 20th ecumenical council and, most famously, defined the doctrine of papal infallibility. (CNS files)

The assembled bishops passed two constitutions. The first was “Dei Filius,” which treated the relationship between faith and reason, and the second was “Pastor Aeternus,” which treated the Church. Both should be seen in the context of the chaotic climate of the day.

“Dei Filius” engaged the rationalists’ claims that human reason was the ultimate arbiter of truth, including the reliability and status of revelation. The decree asserted the supremacy of revelation, arguing that revelation was neither subject to human reason nor contrary to it.

“Pastor Aeternus” defined the doctrines of papal primacy and infallibility as a way of establishing the Church’s authority, stability and independence in a time when those things were openly debated. These definitions did not intend to usurp the authority of bishops or curtail the freedom of Catholics; rather, they sought to capacitate the pope to secure those things.

Properly understood, these teachings are not about power. They illumine a close relationship between Christ and the Church that is manifest in a unique way in the papal office.

The chaotic times that prompted Vatican I also provoked its premature suspension. The council’s agenda called for extensive deliberations on the nature of the Church that would set the teachings on papal authority in their proper context.

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war forced an interruption of the conciliar proceedings in 1870, leaving work on the draft document on the Church incomplete. Though a resumption of the council was considered at least twice in the 20th century, its work was never resumed.

Understanding Vatican I’s context allows us to appreciate its intentions and teachings. The council sought to preserve the Church’s ability to advance its mission in a rapidly changing and often hostile environment. Working from a defensive posture, it produced strong statements about the nature of revelation and papal authority to demonstrate the Church’s ability to overcome the errors of the day.

Yet, the council was unable to complete its work. As a result, scholars often say that Vatican I’s teachings are true but incomplete or one-sided. It is this one-sidedness that motivates some to try to leave the council behind and Google “Vatican II history” instead.

Vatican I is nevertheless part of the larger conciliar tradition guided by the Holy Spirit in which each council is meant to be seen in light of the others. The council provides authoritative teachings, yet its positions find their full expression in their harmonization with other conciliar statements.

For example, Vatican I is largely silent on the role of the bishops in relation to the pope. That silence is not a negation of episcopal power, but represents “unfinished business.”

Vatican II engaged this unfinished business by considering the nature of episcopal collegiality. Therefore, while some try to posit Vatican I’s teachings on the pope and Vatican II’s teachings on the bishops as an either/or choice, in reality, by virtue of the nature of the conciliar tradition, they must be seen as a both/and.

Pope Francis continues this work of bringing greater harmonization to the various forms of ecclesial authority. Pope Francis has called for a “sound decentralization” of Church structures, yet he is clear that moving in this direction requires a deeper understanding of Vatican I’s teachings.

He recognizes that Vatican I is not an obstacle but a necessary and valuable resource for considering how the diversity that comes with decentralization can be facilitated and held together by a central authority in Rome.

Viewed in the context of its own day and as part of the larger tradition, we can recognize that Vatican I’s teachings are less rigid than generally presumed and meant to be seen as part of a larger whole.

One hundred and fifty years later, we cannot afford to leave this historic event in the past because, properly understood, it holds key insights for the future.

Colberg is associate professor of theology at St. John’s School of Theology and Seminary in Collegeville, Minnesota. She is author of the book “Vatican I and Vatican II: Councils in the Living Tradition.”

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.