November 15, 2019 // Vatican

Papal infallibility: fresh perspectives

By Kristin Colberg

The 150th anniversary of the opening of the First Vatican Council will fall on Dec. 8. Most people know little about Vatican I except that it defined papal infallibility. Few doctrines have generated as much debate and tension as this one.

Controversies concerning the pope’s infallible teaching authority often lead to misunderstanding or dismissal of the teaching and the council altogether. The council’s sesquicentennial invites renewed explorations of papal infallibility to appreciate better its meaning and power to illumine questions in the Church today.

Vatican I took place between December 1869 and October 1870. Pius IX convoked the council as a bulwark against modern developments including rationalism, atheism and relativism, which sometimes cast doubt on the Church’s temporal powers and spiritual authority.

In addition to these external threats, the Church also struggled with internal debates about the authority and purpose of councils in relation to papal authority. These external and internal traumas engendered an extremely defensive posture in Rome.

For many, clarifying the pope’s authority seemed to provide an effective tool for dealing with both sets of challenges.

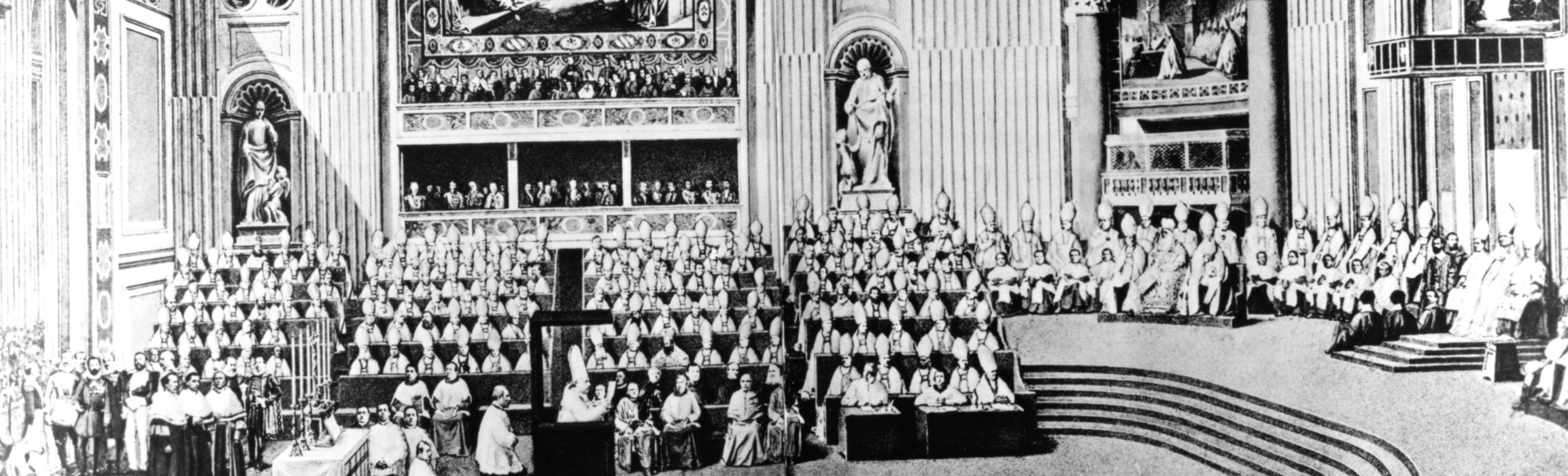

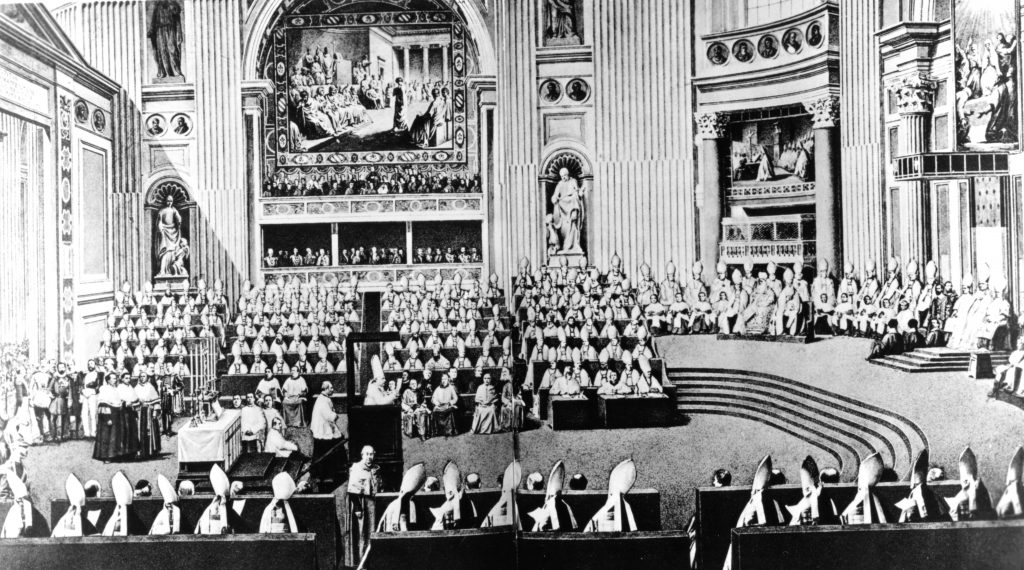

Dec. 8, 2019, will mark the 150th anniversary of the opening of the First Vatican Council. Most people know little about Vatican I except that it defined papal infallibility. (CNS files)

When the council opened, it sought to develop a comprehensive document on the nature of the Church and its jurisdictional power in response to contemporary threats. However, soon after the conciliar deliberations began, it became clear that military conflict brewing in the region would prevent the bishops from completing their entire program of work.

Anticipating the limited time available, the council fathers chose to begin deliberations on the Church with the topic that had generated the greatest interest: papal infallibility.

A minority of bishops, approximately 20%, opposed this starting point as inconsistent with the Church’s tradition of aligning papal authority with that of the whole Church and the bishops in particular.

Most in the minority agreed that the pope could teach infallibly under certain circumstances, but they disagreed with the council’s treatment of this issue as a stand-alone topic and questioned whether defining this matter in the present climate would further alienate the Church.

A majority of the bishops, however, favored moving forward with a definition. Most in this group conceded that considering papal infallibility in this manner was not ideal, but reasoned that it was necessary given the exigencies of the day.

Most in the majority acknowledged that it was normal and appropriate for the pope to consult the universal Church when formulating definitive teachings, yet they did not want to formalize this consultation as a requirement for fear that it would hinder the pope’s ability to act in decisive moments.

Among the majority were a small group of “Ultramontane” bishops who sought to express the doctrine in the most extreme way possible so that the pope’s ability to teach without error was absolute, separate and personal.

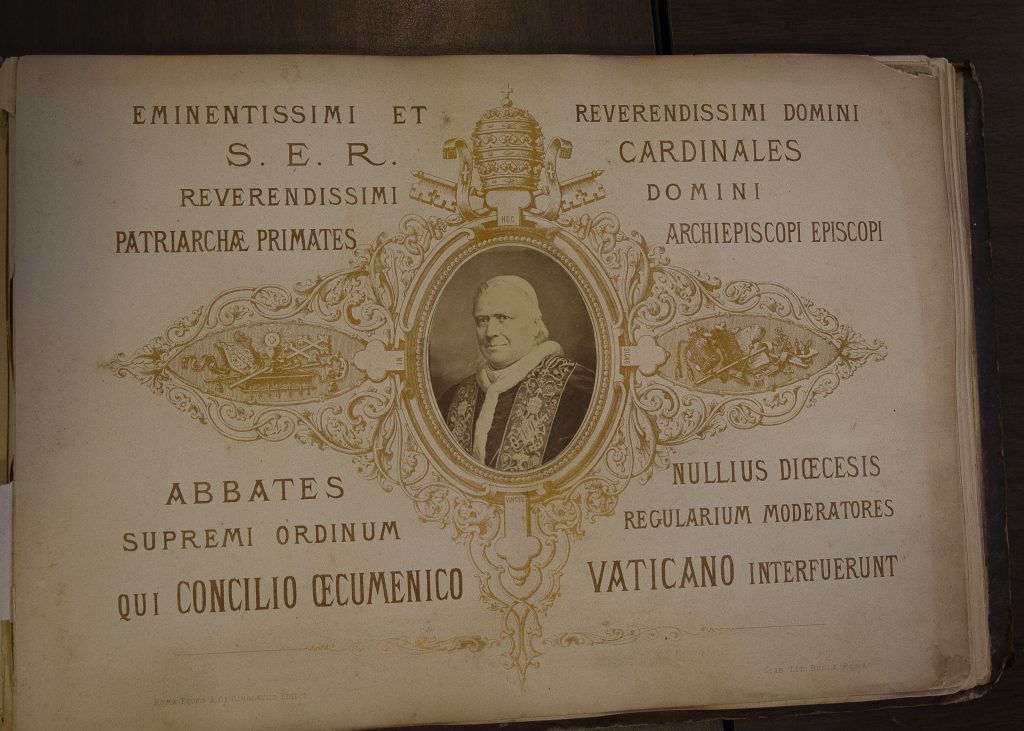

Pope Pius IX is seen in this First Vatican Council album archived with the Archdiocese of Washington. Papal infallibility is not so much about the pope as it is about the love Christ has for the church and his enduring promise to dwell in it and guide it. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)

Vatican I’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, “Pastor Aeternus,” was promulgated on July 18, 1870, following a vote of 533 to 2. Many of the minority bishops had left Rome ahead of this session to avoid voting against a teaching supported by the pope and their brother bishops.

Two months later, on Sept. 20, 1870, Rome’s walls were breached during the Franco-Prussian War and consequently, on Oct. 20, 1870, the council was suspended.

Vatican I is often thought to present an extreme view of papal infallibility, whereby the pope can teach on any topic without restriction. People generally think that the view of the small fraction of Ultramontane bishops prevailed. However, upon examination, it is clear that Vatican I sets distinct limits on papal infallibility.

“Pastor Aeternus” states: “When the Roman pontiff speaks ‘ex cathedra,’ that is, when, in the exercise of his office as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, in virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole church, he possesses, by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter, that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer willed his church to enjoy in defining doctrine concerning faith or morals” (4).

The pope’s infallible authority is not absolute; rather, “Pastor Aeternus” limits its scope to instances where the pope defines a doctrine related to faith and morals to be held by the entire Church. It is not separate from the Church. It is a gift Christ wills for the benefit of the entire Church.

Finally, infallibility is not said to belong the pope “personally,” as if individually possessed. Instead, the infallible teaching office belongs to the pope in the exercise of the apostolic office of Peter.

The dogma of papal infallibility is not about power. It articulates a close and reliable relationship between Christ and the Church in the Petrine office that affords the Church protection, stability and access to truth.

Even though “Pastor Aeternus” does not offer a comprehensive decree on the Church as the council originally envisioned, it is nevertheless a document about the Church and its essential role in advancing God’s saving work.

Papal infallibility reflects the fact that a fundamental aspect of God’s salvific plan is manifest in the Church’s structure and, in particular, in the Petrine ministry.

It is often said that every Catholic teaching about Mary is always, fundamentally, a teaching about Christ. The same is true of teachings about the pope.

Papal infallibility is not so much about the pope as it is about the love Christ has for the Church and His enduring promise to dwell in it and guide it. The wider historical and theological context of this definition shows that it is not the obstacle that it is often perceived to be.

Instead, Vatican I’s teaching on papal infallibility — formulated a century and a half ago — illumines critical aspects of the Church’s identity that can guide our thinking about ecclesial reform, synodality and the Church’s path into the future.

Colberg is associate professor of theology at St. John’s School of Theology and Seminary in Collegeville, Minnesota. She is author of the book “Vatican I and Vatican II: Councils in the Living Tradition.”

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.