November 4, 2014 // Local

From slavery to the Priesthood: Father John Augustine Tolton

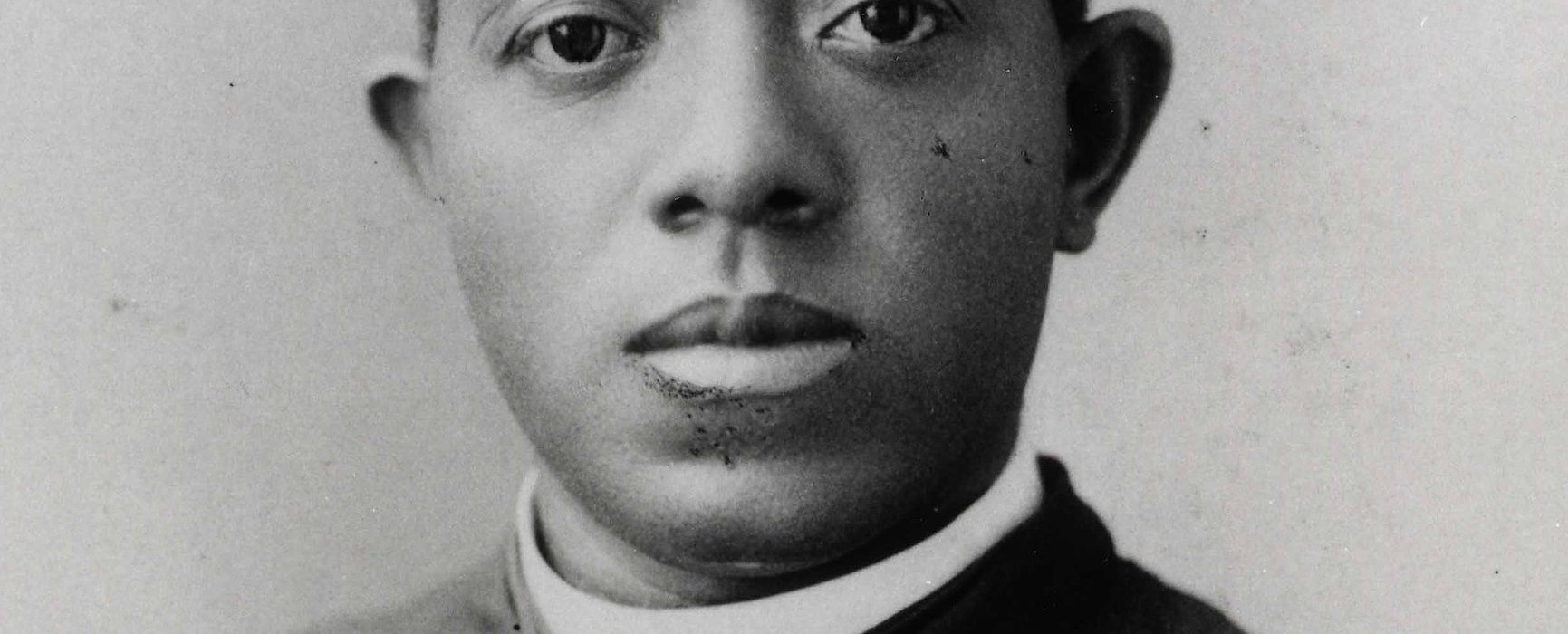

Father Augustine Tolton, also known as Augustus, is pictured in a photo from an undated portrait card. Born into slavery in Missouri, he was ordained a priest April 24, 1886. He served as pastor at St. Joseph Church in Quincy, Ill., and later established St. Monica’s Church in Chicago. Chicago Cardinal Francis E. George has formally closed the investigation into the life and virtues of the sainthood candidate.

By Matthew Bunson

On March 2, 2010, Francis Cardinal George, the archbishop of Chicago, announced that a cause for canonization had been introduced by the archdiocese.

The new candidate for sainthood is truly remarkable for not only was he the first American diocesan priest of African descent but was the son of slaves. His name was Father John Augustine Tolton, and in his short life of 43 years, he endured racial hatred, poverty and intolerance with fortitude and charity. He is today, a model for African American Catholics and a witness to the Church’s welcome to all people, regardless of their color or background.

“The time was not yet right”

Tolton was born on April 1, 1854, into slavery in Brush Creek, Missouri, to the slaves Peter and Martha Tolton. His parents had been married in a Catholic ceremony and made certain that he was baptized, at St. Peter’s Church, a few miles from Hannibal, Missouri.

At the start of the Civil War, his father escaped and joined the Union army, and his mother, in 1863, made the courageous decision to flee Missouri with her three children to the free state of Illinois. Augustine was nine at the time.

Once safely in Quincy, Illinois, Martha found work with her sons in a local cigar factory and took them to Mass in the local German parish of St. Boniface. The family endured great hardship and tragedy, including chronic poverty, the death of Augustine’s brother in 1863, and the news that Augustine’s father had died from dysentery in St. Louis.

Meanwhile, Martha enrolled Augustine in St. Boniface School for the part of the year when business was slow at the cigar factory. Within a month, she was asked to withdraw him by the pastor and the sisters at the school because of anonymous threats and complaints that a black child was studying there. Martha reluctantly enrolled him in a public school, and the family departed St. Boniface’s for St. Peter’s Church in Quincy, where they found a slightly more welcoming environment.

The chief reason for that welcome was the pastor there, a fierce Irish priest named Peter McGirr, who issued the unexpected invitation for Augustine to attend the parochial school at St. Peter’s.

It was Father McGirr also who allowed young Augustine to serve as an altar boy and who first encouraged him to discern a vocation to the Priesthood. Augustine embraced the possibility, but both of them knew how difficult it would be to secure his entry into the seminary. This proved to be the case, and so several priests banded together to begin his preparation anyway. Augustine progressed swiftly. He completed high school and then graduated from Quincy College.

There remained the problem of a seminary. Every application was declined on the basis that “the time was not yet right” for a black seminarian. Undaunted, Father McGirr won the help of the Franciscan Fathers, and through their Minister General secured admission for Augustine into the College of the Propaganda Fide in Rome to become a missionary in Africa.

Tolton later acknowledged the immense debt he owed to Father McGirr, declaring in 1889, “The Catholic Church deplores double slavery — that of the mind and that of the body. She endeavors to free us of both. I was a poor slave boy, but the priests of the Church did not disdain me. It was through the influence of one of them that I became what I am tonight.”

A Missionary to America

In February 1880, Tolton joyously set sail for Rome, and the next six years of intense studies in languages, theology and missiology were the happiest of his life. Finally, on April 24, 1886, he achieved the fulfillment of his dreams: Augustine Tolton was ordained a priest in the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome. On Easter Sunday, he celebrated his first Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica. His life had changed forever, but not in the way he had expected.

The day before he received Holy Orders, Tolton was informed that the Propaganda Fide was not sending him to Africa. Instead, he was heading back to the United States. He was still to be a missionary, but to America, a country that had ended slavery but still did not have one black priest.

For Tolton, the news was shocking. He knew what he was being asked to do. He had grown up facing racial prejudice, and he was acutely aware that returning as a priest would only make him a target of hatred from anti-Catholics and even from some Catholics who were not ready to accept a black man as a priest. Tolton, however, obediently accepted the assignment.

After a joyous welcome home from Father McGirr, he celebrated Mass on July 18, 1886, at St. Boniface Church. In attendance were several thousand people, both black and white.

His first assignment was as pastor to the African-American parish of St. Joseph Church that had been established out of St. Boniface. He proved a gifted homilist, and when whites started attending the parish and seeking his spiritual advice, complaints were made to the local bishop that Tolton was trying to “mix the races.”

In the end, the situation of intolerance became so strident that Father Tolton was forced to ask permission of authorities in Rome to accept an invitation from Archbishop Patrick Feehan of Chicago. Feehan wanted him to serve as a pastor for black Catholics in the city. This solution was accepted by Rome, and on Dec. 19, 1889, Tolton left his family and friends for Chicago and the challenges of a new phase of service.

Father Gus

Around 1882, black Catholics in Chicago had started the St. Augustine Society, dedicated to visiting the sick, providing proper funerals and feeding the poor. Mass for them was celebrated in the basement of Old St. Mary’s Church on 9th and Wabash. With his arrival, Father Tolton became their chaplain.

In 1891, Tolton won permission to move out of the basement by building a church for the African American Catholics of Chicago, what he hoped would be St. Monica’s Church, on the corner of 35th and Dearborn. Even though much of the church was not finished owing to lack of funds, Tolton celebrated the first Mass at St. Monica’s in 1893. What had begun as a tiny flock hidden away in the bottom of a church grew to a congregation of more than 600, and St. Monica’s served as the spiritual center for black Catholic life in the city for decades to come.

Tolton embraced his people with selfless devotion and settled into his role as the first black pastor in Chicago. He was called “Father Gus,” but while he had been accepted by his fellow Chicago priests, his ministry was still largely performed alone among the shocking slums of the city. He worked tirelessly to care for the sick and the forgotten, giving completely of himself to a community still struggling for acceptance and justice. And through it all, he endured intolerance and hatred both for being a black man and a Catholic priest.

A symbol of his new life was the change in living quarters. He had lived initially in a small room on South Indiana Avenue, near St. Mary’s Church. Later, with the help of his congregation, Tolton was able to move into a small house behind St. Monica’s. Significantly, the added space allowed him to invite his mother and sister Anne to come and live with him and so unite the family once more.

As his fame spread he was also invited to speak at national gatherings. In 1889, he gave an address at the First Catholic Colored Congress in Washington, D.C., and he was asked to speak to Catholics in Boston, New York and even as far away as Galveston, Texas. At the same time, he pressed ahead with future plans for St. Monica.

In early July 1897, Father Tolton attended the annual retreat of Chicago priests at St. Viator’s College in Bourbonnais, Illinois. The temperature reached 105 degrees in the city, and while returning to the parish on July 9, he collapsed from the severe heat near Calumet Avenue in Chicago. He was taken to the nearby Mercy Hospital, but he never regained consciousness and died a few hours later. The cause of his shocking death was listed as sunstroke. The stunned black Catholic community bid a loving farewell to “Father Gus,” and his remains were taken to St. Peter’s Cemetery in Quincy.

The achievements of Father Tolton did not die with him. He was cherished among the black Catholics in Chicago and across the country. He also remained a powerful model for young black men seeking to follow his footsteps into the Priesthood and for all priests dedicated to proclaiming Christ’s love in the face of hatred and scorn. America’s first Black Catholic bishop, Harold Perry, SVD, wrote of him, “Father Tolton found his opposition within the Church and among Church people, where compassion should have offset established prejudice and ignorance. It was his lot to disprove the myth that young Black men could not assume the responsibility of the Catholic Priesthood.”

_______________

Prayer for the Cause of Father Augustus Tolton

O God, we give You thanks for Your servant and priest, Father Augustus Tolton, who labored among us in times of contradiction, times that were both beautiful and paradoxical. His ministry helped lay the foundation for a truly Catholic gathering in faith in our time. We stand in the shadow of his ministry. May his life continue to inspire us and imbue us with that confidence and hope that will forge a new evangelization for the Church we love.

Father in heaven, Father Tolton’s suffering service sheds light upon our sorrows; we see them through the prism of Your Son’s passion and death. If it be Your will, O God, glorify Your servant, Father Tolton, by granting the favor I now ask through his intercession, (mention your request), so that all may know the goodness of this priest whose memory looms large in the Church he loved.

Complete what You have begun in us that we might work for the fulfillment of Your kingdom. Not to us the glory, but glory to You O God, through Jesus Christ, Your Son and our Lord. Father, Son and Holy Spirit, You are God, living and reigning forever and ever. Amen

Bishop Joseph N. Perry

Imprimatur: Francis Cardinal George, OMI

Archdiocese of Chicago, 2010

Reprinted with permission from

The Catholic Answer, July/August 2014.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.