January 24, 2017 // Local

Following death of Castro, Pedro Pan refugees recall relocation

Jack, originally Joaquin, Hernandez and his wife, Carol, pose during a recent vacation. Jack was among the wave of young, unaccompanied Cuban refugees who arrived in the U.S. during a two-year period following the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

By Patrick Murphy

They came to Fort Wayne just as the Cold War threatened to worsen — dozens of teenage Cuban boys, slightly bewildered but determined.

The boys were part of Operation Pedro Pan, a plan engineered by the U.S. government, the Catholic Church in Miami and parents anxious to get their youngsters off the island nation after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. The plan, which was terminated abruptly after the Cuban Missile Crisis, saw about 14,000 adolescent boys fly from Havana to Miami, eventually being disbursed to family members and religious organizations in Nebraska, Delaware, New Mexico and other states, including Indiana.

Most were Catholic, but some Protestants and Jews were among the exodus. They arrived unaccompanied, but a large percentage were reunited with family members who were already here or who came to the U.S. later on.

No one seems to recall exactly how many of the boys came to Fort Wayne or how many of them remained in the area. There were likely as many as three dozen who arrived in the Summit City in the early 1960s, many of them then traveling to Florida or another state that had a warmer climate.

The youngsters were close during the exodus. And while many have lost contact over the last half-century, others keep in touch. Each of the Pedro Pan youngsters has his own story, and a few of the boys who first came to Fort Wayne were able to be located to share some of it.

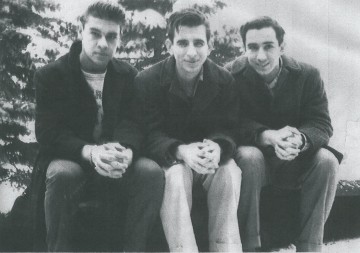

Among the dozens of minors who were flown to Fort Wayne during the Pedro Pan operation of 1959-61 were Jack Hernandez, center, and Michael Barnet, right. Both young men attended Catholic high school and then married, began working and settled in Fort Wayne.

“They were an energetic bunch,” said Mike Serrani, one of the housefathers hired to supervise the new arrivals. They initially stayed at St. Vincent’s Villa on Wells Street, and later at a house in the 1000 block of west Wayne Street. “And most became quite successful,” he said.

“We didn’t like winter,” said Michael Barnet, who was 15 when he arrived in the summer of 1961, among the initial batch of refugees. “But the sisters dressed us warmly, and we got through it.”

Language was a problem, although some of the youngsters had studied English in Cuba. Others took classes in grammar and usage while awaiting transport to their new homes. “I barely understood anything,” said Barnet. Their hosts used hand gestures, he recalled, and sometimes the boys needed things to be repeated over and over and over. “It was hard, but lots of fun” he remembered. “Everybody in school was very understanding.”

Frequently on Sundays, the new arrivals would spend afternoons with families who welcomed them into their homes. Barnet remembered that during these visits they learned more about the U.S. way of life.

After graduation from high school, Barnet took a job at Seyferts Potatoes and became an interstate truck driver. “I enjoyed every minute,” he said. He retired after 37 years.

The high school the young Cubans attended was Central Catholic High School, where they were made to feel at home. “At first, some had some trouble with the language,” remembered Steve App, a 1962 graduate. “But they were welcomed with open arms.”

Following their studies at Central Catholic, Ledo studied accounting for several years at what would eventually become IUPUI. He then enjoyed a career in the wire industry. Now retired, he and wife Sharon enjoy spending time with their children and grandchildren. “I get urge to return (to Cuba) once in a while,” he said, “but I never have.”

Joaquin “Jack” Hernandez, another refugee who landed in Fort Wayne, graduated from Indiana Tech with a degree in mechanical engineering before becoming a supervisor at Navistar. He remembered that while most people were receptive of him and the other Cubans, others weren’t. “I can’t say it was discrimination,” he said, “but they weren’t particularly friendly. We just avoided them.”

One of the teen refugees who relocated from Fort Wayne to Florida was Felipe de Jesus Estevez who became bishop of the Diocese of St. Augustine.

Benet, Ledo and Hernandez, all of whom are now U.S. citizens, said they are grateful to Fort Wayne and the residents who welcomed them. The nuns, priests, parishioners and ordinary people helped their transition to new lives possible, even adventurous and enjoyable, they agreed.

The trio has mixed feelings about efforts to normalize relations with their homeland since the death of Fidel Castro. “They’re a good idea,” said Hernandez, “as long as it’s tied to improving human rights and giving ordinary citizens more of a voice in their government.”

Ledo is more skeptical. “I don’t know that it will make a difference,” he said. “But I hope so.”

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.