March 24, 2010 // Local

Understanding the liturgies of Holy Week, Easter

By Brian MacMichael

Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is observed on the sixth Sunday in Lent, and marks the official beginning of Holy Week. Palm Sunday is meant to commemorate the triumphant entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, when, as the Gospels tell us, the people of the city hailed Jesus as their king.

During this year’s entrance processional with palms from outdoors, Luke 19:28-40 will be read. This is the account of the people of Jerusalem spreading palms before Christ while singing, “Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord. Peace in heaven and glory in the highest.” Of course, this is basis for the “Sanctus” acclamation we sing at every Mass at the beginning of the Eucharistic Prayer.

During the Mass itself, the first reading is from Isaiah, while the second reading will be from Philippians chapter 2 — the famous Christological hymn that begins: “Christ Jesus, though He was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather, He emptied himself, taking the form of a slave. … ” This is a very powerful text that has been the basis for much of the Church’s theological affirmations that Christ was truly God and truly suffered as man. The Eastern Churches see this as the beautiful hymn of the Son of God’s “kenosis,” or voluntary “self-emptying” out of love for sinful man.

Finally, the Gospel this year will be from Luke, with the traditional practice of the priest and others assuming the roles of Christ and the various figures. The narrative spans the time from the Last Supper to the death of Christ.

One might be curious as to why we read the entire Passion narrative on Palm Sunday. In addition to ensuring that those who won’t be attending the Good Friday liturgy may still hear the Passion, a possible Scriptural foundation may be found in the Gospel of Luke, a few chapters before the entry into Jerusalem. In Luke 13:33-35, Jesus says:

“Yet I must continue on my way today, tomorrow and the following day, for it is impossible that a prophet should die outside of Jerusalem. ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how many times I yearned to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, but you were unwilling! Behold, your house will be abandoned. (But) I tell you, you will not see me until (the time comes when) you say, ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.’”

Although this passage is somewhat enigmatic, Jesus utters a prophecy that is reminiscent of the plight of the Old Testament prophets, while also pointing to the fact that he must enter the city to accomplish his mission. This mission, to die as an innocent and sacrificial victim, is the true focus and fulfillment of the triumphant entry into Jerusalem.

In terms of historical development, this feast was known as Passion Sunday in Rome during the days of the early Church, with the focus being on the cross that awaited Christ in Jerusalem. However, in Jerusalem itself, the focus was on a reenactment of the hailing with palms branches. Thanks to the written testimony of such pilgrims as Egeria, who was most likely a fourth-century Spanish nun who kept a journal of the Holy Week liturgies during her visit to Jerusalem, the palm tradition of Jerusalem was brought west, and eventually was blended with the Passion focus, giving us the combination we have today.

It is interesting to note that palms branches used on Palm Sunday are often burned to create the ashes for Ash Wednesday of the following year. There is surely much symbolism in this connection. One might say that the palms are burned to remind us of our mortality and profound need for God’s mercy. After all, the palms are used to hail Christ, but the same people ended up assenting to his crucifixion — and are we not all sinners as well, who also nail Christ to the cross? To use the palm ashes at Ash Wednesday prepares us to enter Lent as a very important season of penitence and preparation to truly welcome Christ into our hearts forever.

Spy Wednesday

Wednesday of Holy Week used to be called Spy Wednesday. The rationale is clear from the day’s Gospel reading from Matthew, in which Judas Iscariot approaches the chief priests and offers to betray Jesus for 30 pieces of silver.

Mass of the Sacred Chrism

Traditionally, on Holy Thursday or an earlier time during Holy Week, the holy oils — the Oil of the Sick, the Oil of Catechumens, and the Sacred Chrism — are blessed by the bishop at a special Mass, and then distributed to churches through the diocese. In our diocese, we celebrate a Chrism Mass on Monday of Holy Week at St. Matthew Co-Cathedral in South Bend, and on Tuesday of Holy Week at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Fort Wayne. The Sacred Chrism will be used to confirm the elect at the Easter Vigil. The Chrism will also be used in the coming months for priestly ordinations, and it is employed for certain sacramental blessings and consecrations, such as the dedication of churches and altars. The Oil of the Catechumens is employed throughout the year for Baptisms, while the Oil of the Sick will be used for Anointings of the Sick.

The Chrism Mass also has a special focus on the priesthood, as the presbyterate comes together to concelebrate with the bishop and manifest their communion with him. During the Mass, the priests renew their commitment to priestly service, dedicating themselves anew to Christ and to service of the local Church, particularly through the sacred liturgy. In this Year for Priests, we should pray for our presbyterate in a special way during Holy Week.

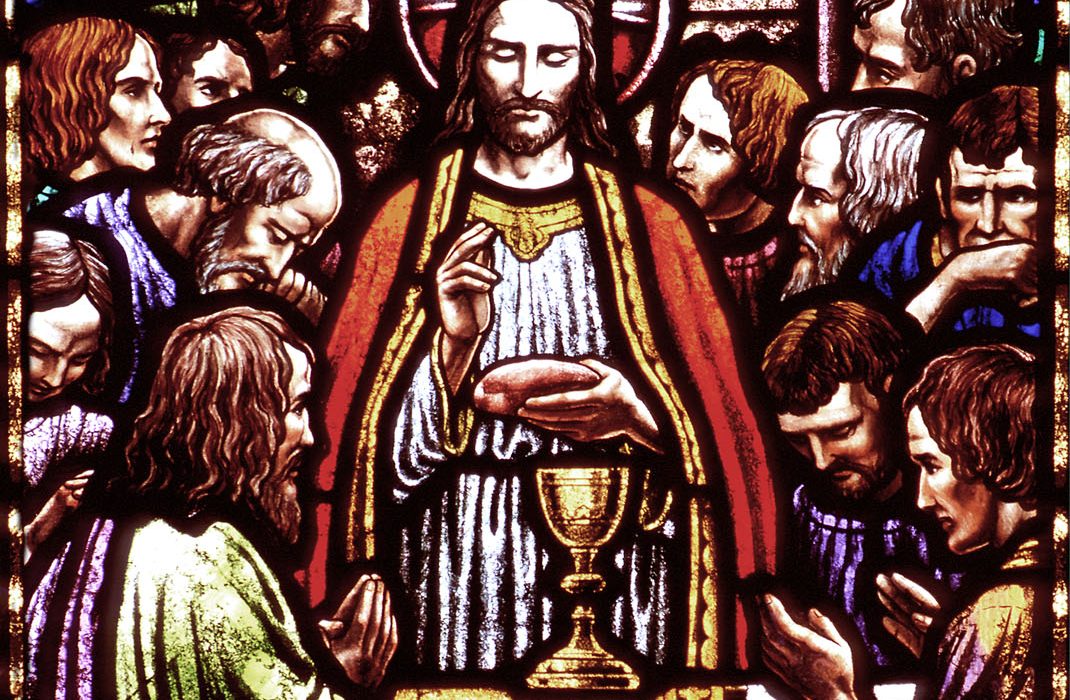

Holy Thursday

The Holy Thursday Mass of the Lord’s Supper is meant to commemorate Christ’s institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper, and it also marks the institution of the priesthood. Holy Thursday is the beginning of the Easter Triduum, which encompasses Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Easter Sunday (“triduum” is Latin for “three days”). The Sacred Triduum is the highest feast in the liturgical life of the Church.

The feast of the Lord’s Supper is also known as “Maundy Thursday.” Some have suggested that the word “maundy” derives from the beginning of a phrase towards the end of the Last Supper account in John’s Gospel: “Mandatum novum do vobis, ut diligatis invicem, sicut dilexi vos … “ (“A new commandment I give unto you, that you love one another as I have loved you.”). — Jn 13:24. In many ways, this phrase is a recapitulation of the entire Gospel, and of Jesus’ fulfillment of the Mosaic Law. At the same time, it is a verbal expression of the powerful message found in Holy Thursday’s Gospel reading, in which Christ washes the Apostles’ feet.

The washing of feet, or the “pedilavium,” is perhaps the most distinctive rite that can be used during the Holy Thursday liturgy. St. John’s Gospel is the only one not to include a Eucharistic institution during the Last Supper account. Instead, it records the foot washing as an instruction for the entire life of community, charity and humility that should govern the Church: “If I, therefore, the master and teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash one another’s feet.” — Jn 13:14. The liturgical reenactment of the footwashing, in which the priest washes and dries several pairs of feet, also has a very deep symbolic meaning associated with cleansing; and its proximity to the Baptism of the elect — those catechumens to be received into the Church at the Easter Vigil — is very appropriate. St. Ambrose, who was bishop of Milan during the fourth century and whose “mystagogical catecheses” are among the Patristic sources that inform our Rites of Christian Initiation today, included the “pedilavium” as part of the Milanese baptismal rite. Moreover, the footwashing rite has come to emphasize the ministerial role of the priesthood instituted by Jesus Christ on Holy Thursday, calling to mind the manner in which He acted as servant to the Apostles, who would become the first priests.

The Holy Thursday liturgy concludes with the solemn transfer of the reserved Blessed Sacrament to an altar of repose, separate from the main altar and tabernacle. The “Pange Lingua,” a beautiful Eucharistic hymn by St. Thomas Aquinas, is chanted as the priest brings the Body of Christ to the altar, where Christians will keep vigil throughout much of the evening and night. This practice recalls the Agony in the Garden, when Christ implores Peter, “So you could not keep watch with me for one hour?” Some keep the pious tradition of visiting up to seven altars of repose in different churches throughout a city on Holy Thursday night. A plenary indulgence used to be attached to this act of devotion and adoration.

There is no formal conclusion to Mass on Holy Thursday. In a sense, the entire Triduum is a single liturgy, commemorating the entirety of the salvific Paschal Mystery — Christ’s Passion, Death and Resurrection.

Office of Tenebrae

A tradition that has been revived in many Catholic churches is the ancient Office of Tenebrae. “Tenebrae” means “darkness” or “shadows,” and is derived from the phrase in the Gospels: “tenebrae factae sunt super universam terram” — “darkness came over the whole land.” — Mt 27:45. It commemorates the withdrawal of the light as Christ died on the cross. Some have described Tenebrae as a sort of funeral for Christ.

The Tenebrae service was originally the combined offices of Matins and Lauds (the first two hours of the daily Divine Office) on Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday — often prayed the night before or around midnight. Today, when used as part of public devotion, it is sometimes conflated into a single service at night. Psalms, hymns and readings are used, including several passages from the Book of Lamentations. The place of worship is gradually stripped throughout the service, often symbolized by the extinguishing, one by one, of candles and lights, until the church is left in total darkness. This is accompanied by a “strepitus,” or “loud noise,” sometimes made by the assembly slamming their books shut or banging on the pews for a few moments, to recall the earthquake that struck the land at the hour of Christ’s death. A single candle may then be reintroduced and left to burn as a promise that the victory of the prince of darkness is only temporary, and that Christ will ultimately and definitively triumph over death.

There is an interesting musical story associated with Tenebrae. During Tenebrae at the Sistine Chapel in the 17th and 18th centuries, the choir would sing an ethereal version of a piece called “Miserere mei, Deus” (“Have mercy on me, O God”), a setting of Psalm 51 attributed to several composers, but primarily to Gregorio Allegri. This piece of Renaissance polyphony was renowned across Europe not only for its beauty, but also for the fact that the music was not permitted to be transcribed or performed anywhere outside the Vatican. The ban was finally lifted after a young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart — then only 14 — attended Tenebrae at the Sistine Chapel and wrote out the entire piece from memory afterwards. If you have heard the “Miserere” performed before, especially in a liturgical context, you are privileged indeed!

Good Friday

Good Friday is the anniversary of Christ’s crucifixion and death. The Gospel of John emphasized this day as the day of preparation for the Passover, with the lambs being slaughtered at noon, the hour in which Pilate presented Jesus to be crucified (Jn 19:14). The strong connection between Jesus and the spotless lamb would have been unmistakable to St. John’s Jewish and early Christian audience.

The Good Friday service usually begins at 3 p.m., the time of Christ’s death. The Gospel is the Lord’s Passion as recorded by St. John. It is important to note that the Good Friday liturgy is not a Mass. Nonetheless, Holy Communion is distributed from the reserved Sacrament of Holy Thursday. Good Friday has several other unique elements, including the solemn intercessions, which include prayers for the unity of all Christians and that the Jewish people and all other non-Christians may come to embrace the fullness of Christ’s truth. One might also recall the manner in which Jesus interceded on our behalf while on the Cross.

This is followed by the Reproaches, in which God addresses His people, asking why we have betrayed Him and remained faithless, despite all His works on our behalf. The Reproaches are sung, and are drawn from both Old and New Testament texts. The response to the Reproaches is a “Trisagion” (Greek for “thrice-holy”): “Holy is God! Holy and strong! Holy immortal One, have mercy on us!”

The Reproaches are sung during the veneration of a crucifix, whose image of Christ’s crucified body makes it a particularly fitting icon on this day. Churches that are privileged to have a sliver of the True Cross display it and allow the assembly to come forward and venerate it according to personal piety. This tradition is very ancient — in fact, there is a story from the early Church of someone coming forward to kiss a sizable portion of the True Cross, but instead biting a large chunk out in an attempt to steal a piece of this incomparable relic.

It is a fairly universal practice to observe the Stations of the Cross in the evening on Good Friday. The stations are also prayed on Fridays throughout Lent, and can actually be done on any Friday during the year. But the Good Friday Stations have a certain primacy for obvious reasons. In Jerusalem, Christ’s Way of the Cross is followed along its original path, called the “Via Dolorosa” (“Way of Suffering”) or the “Via Crucis” (“Way of the Cross”). In Rome, where pilgrimage to the historical sites was not possible, there are traditional “stational churches” that are meant to be visited — one on each day of Lent. In addition, many landmarks and relics were actually moved from Jerusalem to Rome, to facilitate devotion. An example is the “Scala Sancta” (“the Holy Stairs”), which are recognized as the steps Jesus stood on while at trial before Pilate, and which were brought to Rome from Jerusalem by St. Helena in the fourth century. Now found at the Lateran Palace, it is a common devotional practice for pilgrims even today to ascend the stairs on their knees and in prayer.

Our practice of placing 14 Stations of the Cross in our churches is a sort of combination of how devotion developed in Jerusalem and Rome. We walk from station to station as a type of pilgrimage, engaging in a deep and personal reflection on the sufferings of Christ.

When contemplating Good Friday, it is true that Christ’s death is an event of unparalleled tragedy and sorrow. However, the Son’s death on the cross is also His exaltation on the cross. In a very real sense, the cross is Christ’s throne, from which God has triumphed over sin. The remainder of the Triduum unveils the full reason for our joy.

Holy Saturday

Holy Saturday is a relatively “quiet” liturgical day until the start of the vigil, but it does carry profound theological meaning. It is easy to neglect the fact that, while Christ’s body lay in the tomb, His soul descended into hell. We profess this in the Apostles’ Creed, one of the earliest doctrinal statements of the Church. Father Hans Urs von Balthasar, a great Catholic theologian of the 20th century, interestingly proposed that Christ’s descent into hell was absolutely fundamental to fulfilling the redemption of the totality of human existence — including death itself. Death, as an effect of original sin, is not a part of created human nature; but even humans justified by grace must still die as a consequence of that sin. According to von Balthasar, Christ had to take on the complete experience of death, despite the fact that it was completely alien to Himself as the Son of God. As such, His undergoing of a real death and true lifelessness was much deeper than that of any mere human being. And in the same paradoxical sense in which Christ’s hanging upon the Cross on Good Friday is actually an exaltation, Christ’s descent into the darkest reaches of death on Holy Saturday is actually the triumph of life-giving love over death. By entering into radical solidarity with the dead out of self-emptying love for the Father and for sinful man, Christ removes death’s finality and enables the dead to have communion with God.

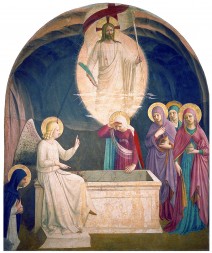

Time-honored Christian iconography depicts the victorious Christ in Hades liberating the righteous souls of those who had died before Christ’s time, and who were awaiting His coming before entering into Heaven. Adam and Eve are typically depicted as the first to accept Christ’s outstretched hand. With the Resurrection of Christ’s body (and with Mary’s bodily assumption), Christians also have the promise that their bodies will be resurrected and glorified at the end of time, when Christ will come again at the Last Judgment to establish the new heavens and new earth.

Fasting is a very important part of the time between Holy Thursday and Easter. Some traditions — especially in the Eastern Churches — allow for almost no eating at all until we have ushered in Easter. However, this period of fasting may be described as more anticipatory than penitential. Some have described it as akin to the fasting that comes naturally before great events in one’s life. For example, many are not hungry on the morning of their wedding day. We, then, are fasting in joyful anticipation of the Resurrection.

Easter Vigil

Commencing at nightfall on Holy Saturday, the Easter Vigil — or the “Great Vigil” — is the high point of the Easter Triduum and of the entire liturgical year. It is at this time that the Church keeps vigil and rejoices as Christ rises from His tomb with the arrival of Easter.

The Easter Vigil was at the forefront of Christian initiation in the early Church, since it was the time in which the elect were baptized, given their white garments, and welcomed to the Eucharist. But the practice became lost, such that there actually was no true Easter Vigil until Venerable Pope Pius XII began instituting a number of liturgical reforms in the 1950s. In fact, Holy Thursday, Good Friday and the Vigil were all celebrated on the mornings of Thursday, Friday and Saturday. A main reason was the Tridentine fasting regulation, which strictly forbade that any food be eaten between midnight and the reception of Holy Communion at Mass that day. As such, it was impractical to have evening Masses. When Pius XII loosened these regulations, it allowed for the Holy Week liturgies to be situated at much more appropriate times, lending a greater authenticity to the celebrations. Moreover, reforms after the Second Vatican Council restored the character of the Vigil as one of Christian initiation.

The Easter Vigil today consists of four parts: 1) The Service of Light, 2) The Liturgy of the Word, 3) The Liturgy of Baptism, with Christian Initiation (including Confirmation) and the Renewal of Baptismal Promises, 4) The Liturgy of the Eucharist.

The Service of Light begins with “Lucenarium” (from the Latin word for “light”), when the Paschal Candle, lit from the Easter fire outside the church, is brought into the darkened church building. The candle is dipped into the font that will be used to baptize the elect, symbolizing Christ sanctifying the waters. The “Light of Christ” dispels the darkness, and the flame is spread to the candles of the individual Christians gathered in the Church. The Paschal Candle itself will be used throughout the season of Easter, and especially for baptisms and funerals during the coming year. When light has been restored, the magnificent and ancient text of the “Exsultet” is chanted. The English translation begins: “Rejoice, heavenly powers! Sing, choirs of angels! Exsult, all creation around God’s throne! Jesus Christ, our King, is risen! Sound the trumpet of salvation!”

The Liturgy of the Word includes seven Old Testament readings, although that number can be shortened for time constraint reasons. Prior to Pope Pius XII’s reforms, there were 12 Old Testament readings. The current readings include selections drawn from Genesis, Exodus and prophetic texts — all alluding to creation and redemption. Then the church bells are rung and the Gloria is sung, marking the end of the expectant vigilant period and a rousing elevation of our Easter joy. Following a reading from Romans, the Alleluia returns from its Lenten absence to herald the Resurrection Gospel: “Why do you seek the living one among the dead?”

The subsequent Rites of Initiation begin with a Litany of the Saints, followed by the public Baptism of those who have completed their catechumenal journey and are now undergoing death and rebirth in Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit working through the water. Afterwards, the newly baptized and those previously baptized who are now being brought into full communion with the Catholic Church receive the Sacrament of Confirmation, using the Chrism oil consecrated earlier in the week. All those in the congregation then renew their baptismal promises to reject Satan and remain faithful to God, and the assembly is sprinkled with baptismal water.

The first Mass of Easter then continues with the Liturgy of the Eucharist, and the newly baptized are permitted to join their brothers and sisters in Christ as they receive the Body and Blood of our Resurrected Lord for the first time.

Easter Sunday

Masses during daylight on Easter Sunday typically don’t contain as much splendor as the Vigil, but they are extraordinary celebrations nonetheless. The Gospel is always taken from John chapter 20, in which Mary Magdalene finds the stone removed from Christ’s tomb and runs to tell Peter and the other disciple, who return to find the tomb empty. A wonderful liturgical practice that is always done on Easter Sunday is the use of the Easter Sequence, “Victimae Paschali Laudes” (the title is from the first line, which translates as “Christians, to the Paschal Victim offer your thankful praises”) immediately before the proclamation of the Gospel. The sequence is a very ancient tradition, and is exceptionally beautiful when sung — especially in the original Latin chant form, which is not very difficult.

The Easter Triduum officially ends with Vespers (Evening Prayer) on Easter Sunday, but the solemn feast of Easter is celebrated for eight days, called the Easter Octave. The eighth day, the Second Sunday of Easter, has recently also become known as Divine Mercy Sunday. The concept of the “Eighth Day” is very important in Christian theology and liturgy. Six was considered a number of imperfection by Jews and Christians, while seven was the perfect number — for instance, God rested on the seventh day of Creation, which became the Sabbath. The “Eighth Day,” as a day beyond even the seventh, is known as the “eschatological” day (derived from “eschaton,” the Greek word for “last”) — it is the day of Christ that points to the end of time and the fulfillment of God’s Kingdom. Sunday was often referred to as the “Eighth Day” in the early Church, and the eschatological character of the day and of the number represents the Christian anticipation of Christ’s “Parousia,” or Second Coming. Baptisteries and baptismal fonts were and still are constructed to be octagonal, indicating the eschatological reality of sacramental death and new life — eternal life — in Christ.

During the Easter Octave, there is a long-standing tradition of Christians exchanging a variety of Easter greetings. One might say, “Christus resurrexit!” (“Christ is risen!”), and another would respond with either “Vere resurrexit!” (“He is risen indeed!”) or “Resurrexit sicut dixit!” (“Risen just as He said!”) or “Deo gratias!” (Thanks be to God!”).

Easter Sunday in the West falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox. In terms of date, this can be anywhere from March 22 to April 25. In his superb book, “The Spirit of the Liturgy,” written while he was still a cardinal, Pope Benedict XVI discusses the timing of Easter. The date of Easter not only historically had a relationship with the date of the Jewish Passover, but has come to express the cosmic significance of the Lord’s Resurrection. By celebrating Easter on a Sunday (the “Eighth Day”) after the first full moon (the fully “risen” moon) of spring (a season of renewal), Christians express the power and universality of sacred time, uniting the rich symbolism of the solar and lunar calendars.

The Easter season lasts 50 days, up until Ascension Thursday (observed on Sunday in much of the United States), is followed 10 days later by Pentecost Sunday.

As we can see, there is much more to the commemoration of Christ’s Passion, Death and Resurrection than just Easter Sunday, or even Holy Thursday and Good Friday. The Easter Triduum and all of Holy Week are a very integrated expression of and participation in the Paschal Mystery that we celebrate every Sunday. By immersing ourselves in the Church’s liturgical life, we spiritually bind ourselves more fully to Christ our Head. We can then better serve as joyful witnesses while we accompany tens of thousands of people — in the United States alone — who will enter into the sacramental life of the Catholic Church during Easter this year.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.