July 12, 2021 // Diocese

Teacher’s book explores 1963 MLK visit to Fort Wayne

When he was 15 years old, Christopher Elliott joined his father to watch a PBS television special on the 20th anniversary of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech.

“It was the first time I had heard the speech,” recalled Elliott, now 52 and a teacher of world and U.S. history at Bishop Luers High School in Fort Wayne.

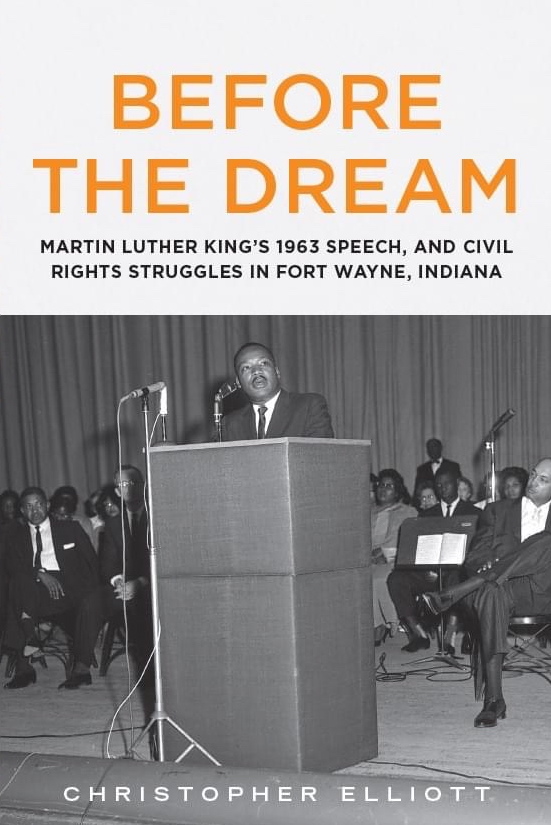

King’s words inspired an interest in the civil rights movement that still drives Elliott today. He explores the topic in his first book, “Before the Dream: Martin Luther King’s 1963 Speech, and Civil Rights Struggles in Fort Wayne, Indiana.”

Provided by Christopher Elliott

The cover of Bishop Luers High School history teacher Christopher Elliott’s book on Fort Wayne civil rights history features a photo of the late Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking during his 1963 visit to Fort Wayne. The book is set for release July 26 and is available to preorder at Barnes & Noble bookstores in Fort Wayne and online at Amazon.com. Retail price is $22.99. He also hopes to make it available at other local retailers. Check for more information on Twitter at @chriselliottFW.

The book, which is scheduled for release July 26, focuses on King’s visit and speech in 1963 in Fort Wayne, the civil rights movement in the city at that time, and civil rights progress in the city and nationally from the 1960s through the tumultuous year of 2020.

Racism goes against Christian and Catholic value, Elliot knows. “Christianity tells us we should treat each other well.”

“Every racist act — every such comment, every joke, every disparaging look as a reaction to the color of skin, ethnicity or place of origin — is a failure to acknowledge another person as a brother or sister, created in the image of God,” the U.S. Catholic bishops said in late 2018, in “Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love, A Pastoral Letter Against Racism.”

The bishops reinforced that position last year as racial violence and police killings of people of color sparked protests around the nation, including Fort Wayne.

“I think it is important to realize the civil rights movement is still going,” Elliott said. “I think we have not made as much progress as I thought, and a lot of others thought.”

Elliott said a combination of factors led him to write his book.

In mid-April 2020, he and most Americans sheltered in place to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. He taught his Bishop Luers classes from home and had a little extra time in his day. Then the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, a nonprofit organization that encourages K-12 history education, announced plans to create a civil rights calendar featuring local communities’ history.

He started work on a brief item for the calendar about MLK’s 1963 visit to Fort Wayne. The trip and speech had come after an invitation from local Black leaders.

Elliott thought there was a bigger story in MLK’s visit.

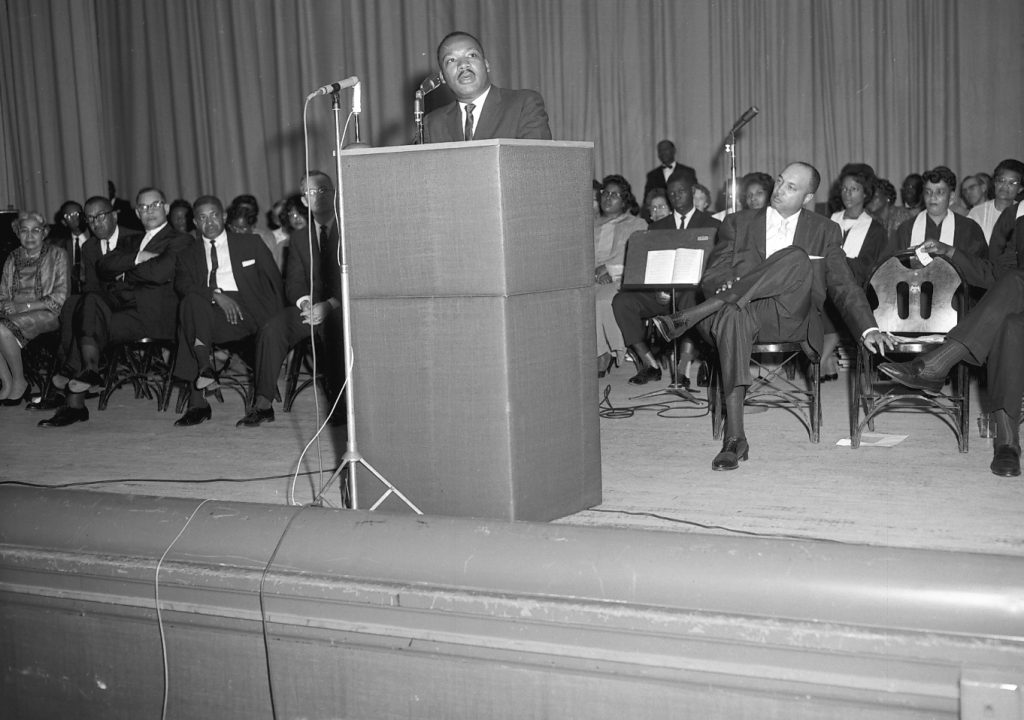

The Journal Gazette | Fort Wayne, Ind.

Late civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke June 5, 1963, in Fort Wayne. Bishop Luers High School teacher Christopher Elliott explores that visit and the civil rights movement in Fort Wayne and nation in a new book, “Before the Dream: Martin Luther King’s 1963 Speech, and Civil Rights Struggles in Fort Wayne, Indiana.”

King spoke June 5 at what was then the Scottish Rite Auditorium in downtown Fort Wayne. The building now is owned by University of Saint Francis and is known as the USF Robert Goldstine Performing Arts Center.

King, already known nationally as a civil rights leader, called for an end to racial segregation and for freedom for Black Americans, local news coverage reported. The remarks took place less than three months before his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on Aug. 28, 1963, during the March on Washington in Washington, D.C.

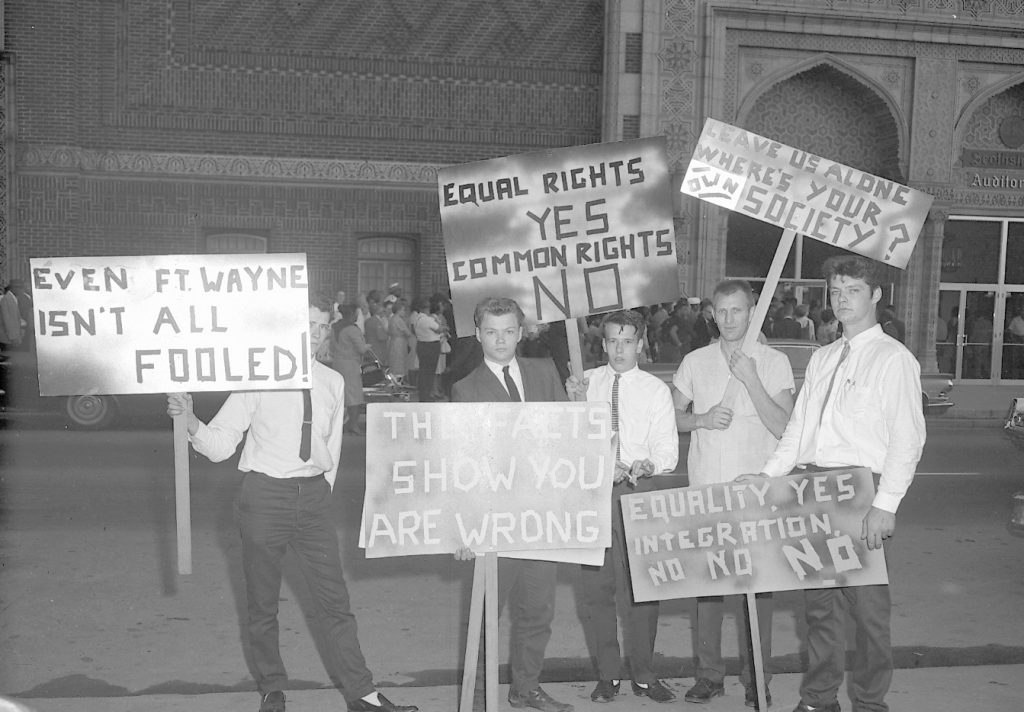

The Journal Gazette | Fort Wayne, Ind.

Protesters identifying themselves as “Citizens for Equality Through Separation” marched across the street from the Scottish Rite Auditorium as Martin Luther King Jr. gave his 1963 speech. A group spokesman said they were “rightists.”

“Dr. King’s visit to Fort Wayne came at a very crucial time in history,” said Bennie Edwards, president of Fort Wayne’s Martin Luther King Jr. Club and one of the local people Elliott interviewed while researching his book. The MLK Club promotes and honors King’s legacy through community activism, youth engagement and multicultural educational activities, its mission statement said.

“His (King’s) visit changed Fort Wayne forever,” added Edwards, who said he is looking forward to Elliott’s book. “It got us interested in what was going on in the South and all over the country.”

To gather information to write the book, Elliott pored over news coverage and materials in the archives of the Journal Gazette and The News-Sentinel, the major local newspapers in Fort Wayne during the period covered in the book. He researched material at the Allen County Public Library.

The Journal Gazette | Fort Wayne, Ind.

Levan Scott, Frontiers Club secretary, left, and Dr. Allan O. Wilson, Frontiers president, right, welcome the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King and Ralph D. Abernathy, second from right, before a speech in Fort Wayne June 5, 1963.

He tracked down and interviewed local civil rights leaders from the 1960s or their surviving relatives, such as Marshall White, son of late local civil rights leader the Rev. Jesse White. Elliott also found and interviewed people who attended King’s speech, including former Fort Wayne Mayor Paul Helmke, who was then a boy.

Information for more recent history covered in the book came from internet research. Elliott also organized a Zoom videoconference meeting with several Fort Wayne Black leaders to discuss current issues, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, racial profiling by law enforcement and redlining in housing discrimination.

“There was a wealth of information available,” Elliott said. “It was a labor-intensive process, but I enjoyed it.”

In addition, he joined the Fort Wayne MLK Club’s board of directors. He began working with a coalition organized through the club that seeks to have Calhoun Street in Fort Wayne renamed in honor of King rather than John C. Calhoun, a former U.S. vice president and Southern congressman who also was a slave owner.

Overall, Elliott found racial prejudice in Fort Wayne “probably was not as hostile as in the South. We did not have examples of violence.” However, local leaders still had to push to ensure people of color received equal treatment at local movie theaters and restaurants.

He also found fascinating the extensive negotiations that took place between the late Rev. Clyde Adams, a local civil rights leader, and the owner of the former Van Orman Hotel.

Here’s Elliott’s account of those meetings included the following: that for much of its life before demolition in 1974, the Van Orman had been one of the leading places to stay in downtown Fort Wayne. Adams and other local Black leaders wanted Martin Luther King and those traveling with him — including civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy — to stay at the Van Orman during their 1963 visit to Fort Wayne.

The hotel owner reportedly previously refused to allow Black people to stay there. After conversations with Adams and some encouragement from the Fort Wayne Police Department, the Van Orman owner reportedly decided MLK and his group could stay there, but they couldn’t eat in the hotel restaurant.

Adams went back to the hotel owner again. The owner reportedly relented and opened the restaurant to all people.

“One of the problems I believe we have with race relations is too many white Americans already have their mind made up,” noted Elliott, who said he feels fortunate to have a number of friends who are Black. “They think they understand the Black experience, but they don’t.”

During last summer’s protests, for example, “I heard white people say it was awful what they were doing — burning down buildings,” Elliott said. “Nobody condones burning buildings or violence. You have to understand where the anger was coming from.”

He believes white people can gain a better understanding if they listen to people of color talk about their experiences.

“I think people will stop jumping to conclusions as much,” he added. “Bigotry is rooted in ignorance.”

Kevin Kilbane

History teacher Christopher Elliott of Bishop Luers High School in Fort Wayne has written a book exploring the civil rights movement from the late Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to Fort Wayne in 1963 through the events of 2020.

Bishop Luers High School teacher Christopher Elliott’s book, “Before the Dream: Martin Luther King’s 1963 Speech, and Civil Rights Struggles in Fort Wayne, Indiana,” is available for preorder at Barnes & Noble bookstores in Fort Wayne and online at Amazon.com. Retail price is $22.99. He also hopes to make it available at other local retailers. Check for more information on Twitter at @chriselliottFW.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.