October 10, 2017 // The Human Condition

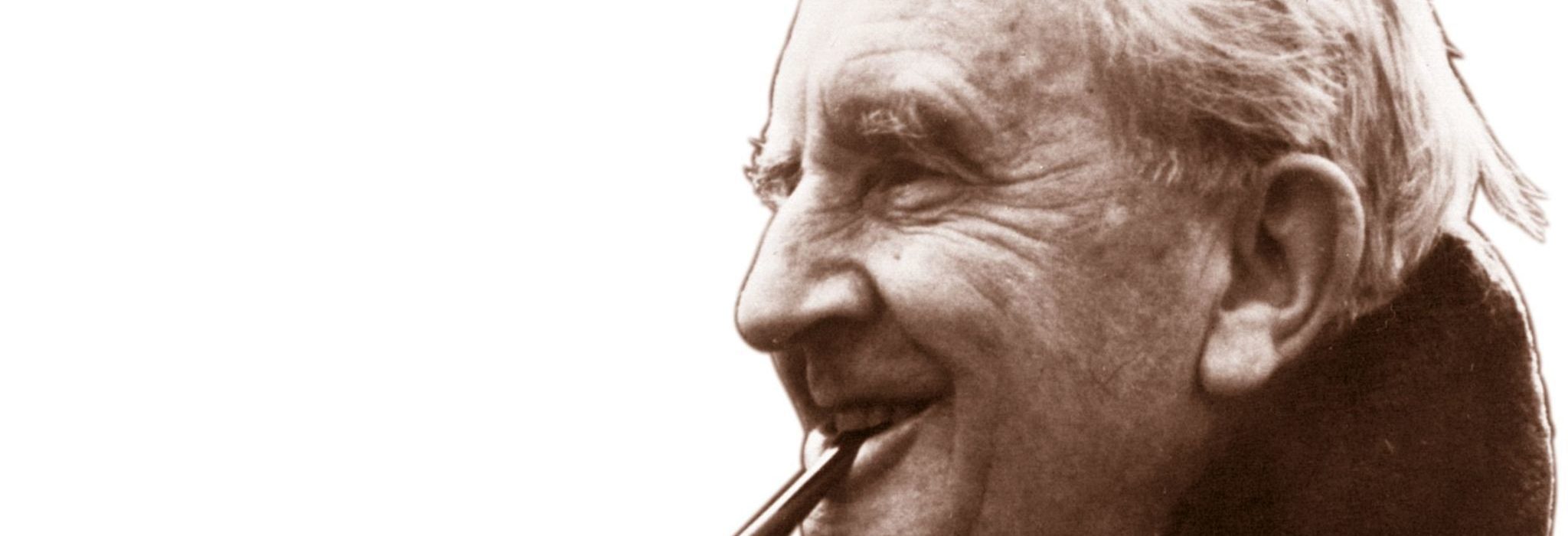

Some takeaways from Tolkien

I have to confess, with some embarrassment, that one of my human deficiencies is that while I read quite a lot, I am not much of a fiction reader. So, one of the goals I had set for myself this past summer was to sit down and read Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings.” While I am familiar with snippets from the movies, I must confess I had never read the book(s). But among the seminarians with whom I live and work it is a very well-loved read, and this is an instance where they served as role models and an inspiration to me.

I will say, it was an easy and most pleasant experience. I had several “conversation partners” during the summer — friends who had read the books already — and so I was blessed with many insights from their reading that enriched my own. In fact, it was such a pleasure I picked up and read “The Hobbit” when I completed the trilogy.

There are any number of books on the sacramentality and symbolism in Tolkien’s Middle-earth, and my own observations neither do justice to the work nor exhaust the innumerable insights one can glean from reading these magnificent books. What I offer is a few musings on elements of our life as believers that were brought into greater relief (in some cases, quite beautifully) by my experience of reading them:

Evil is insidious; yet, grace is even more subtle. Any of us who has tried to live the life of faith and virtue knows how wily the evil one can be. In addition to the feebleness owing to our own mortal condition and the allurements in the world around us, the enemy is quite cunning and will do his best to use our own strengths against us, dealing in half-truths, false assumptions or inferences we draw, all the while keeping us oblivious to his presence and work. Although grace is even more subtle, God, in his providence, can make use even of our own foolishness and weakness, to our advantage and the salvation of the world. I was struck in these books that what to the reader (and the characters) signaled disaster and defeat became the very means of victory. In short, God will work to save us in ways we often cannot perceive directly, and more often than not in spite of ourselves.

We need each other; boy, do we need each other. The very title of one of the volumes invokes the notion of fellowship; in the language of the New Testament that would be “koinonia” or “communio,” one of the earliest designations of the community that is created not primarily by our choice, but by Christ in and through his sacrificial love. We can bristle against one another, misunderstand one another, take each other for granted, but in the end, life in the church is the only way we can make it. When we seek to make it on our own, when we separate ourselves from fellowship, we impede our own progress. Period. Over-romanticized notions of individualism and achievement dominate in our culture, but despite the inherent challenges (“where two or three are gathered, there’ll usually be a problem”), the alternative is much worse. Fidelity — to our friends, our spouse, our fellow-parishioners — is essential if we are to make it. The fellowship that is forged among the new friends of Middle-earth — a bond that cut across races and nations — is an essential element of the story. Despite initial (and at times, recurring) mistrust, misapprehension and failure, the bonds that are forged while sharing a noble task deepen and in fact sustain the characters throughout. Samwise Gamgee, Mr. Frodo’s right-hand man, so to speak, is at once Peter (he’s terribly impetuous, even as he looks out for his friend), beloved disciple, and Simon of Cyrene, at one point carrying Frodo to his appointed end. These are books worth reading with friends and talking about with friends: I suspect such friendship will only be deepened by the shared venture, a fellowship of sorts, forged by shared reading.

God’s providence is real, but more often than not, unknown to us. Near the end of “The Hobbit,” when Bilbo’s adventure there and back again had come to an end, he expresses surprise to Gandalf the Wizard at the realities he had experienced that had been sung of long before in lore. “You really don’t suppose,” Gandalf admonishes Bilbo, “that all your adventures and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit?” As Catholics, we recognize that God is able to make use of our freedom in the service of his plan, and while so many things may to us appear fluky or happenstance, nothing happens apart from the will of God. Each of us, as the wizard tells Mr. Baggins, is “only quite a little fellow in a wide world after all.” What benefits us in this overarching providence is never solely or merely for us. We are part of a larger organism comprised of bodies and souls that St. Paul calls Christ’s body, growing by grace to full stature.

As I concluded the “Return of the King” I felt as though I was saying farewell to friends. From late May to late July, many of these characters had become my companions, and I savored the final pages. Being something of a sentimentalist at heart, I read through teary eyes Gandalf’s words to the members of the fellowship as their venture together drew to an end: “Well, here at last, dear friends, on the shores of the Sea comes the end of our fellowship in Middle-earth. Go in peace. I will not say do not weep: for not all tears are an evil.” Good to know.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.