June 24, 2022 // Uncategorized

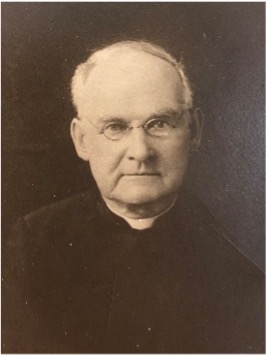

Servant of God, Brother Columba (John) O’Neill, CSC (1848-1923)

On 5 November 1848, John O’Neill was born in Mackeysburg, Pennsylvania, to parents Michael and Ellen (McGuire) with a congenital foot abnormality. The child was baptized sub conditione just two days later, on 7 November, because it was not expected that he would live. To the surprise of the O’Neill family and their intimates, John lived seventy-five years—a life marked by humility and a healing sanctity.

Immigrants to the United States from the Irish city of Kilkenny, Michael and Ellen had a total of six children: Patrick being the first-born; the next being Eliza; then James and Terry being the third- and fourth-borns, respectively; John being the fifth, followed by the baby of the family, Dennis. Though unlearned, Michael and Ellen were faithful Catholics and raised their children in the faith. Seeing that Mackeysburg was an epicenter for quarrying at the time, Michael seized the opportunity to learn and instruct his sons in the business of mining for coal.

The men of the O’Neill household were expected to work in the coal mines with their father, who was, in John’s words, “as strict as the blazes” and was known to whip his children “for every little thing.” John was especially close to his mother during his early years, for John “had fallen entirely” into her care when “Michael O’Neill was swinging his pick into the black bowels of the earth hundreds of feet below the ground.” John’s long-suffering mother spent “hours with [John] every day” teaching the child to walk, which was especially difficult on account of the child’s odd feet. Nonetheless, John—who eventually developed a “fairly graceful” gait—was determined to be like the other men in the family and work in the coal mines, even if doing so meant denying the real pain that such work would cause him.

As a youth John suffered countless humiliations (especially from his austere father), and throughout his life he grew friendly with suffering and rejection. Not only was John humiliated at home and at school on account of his unhandsome countenance and evident frailty, he was also, unable to wield the pickaxe, which was a symbol of manhood among blue-collar families in 19th-century Pennsylvanian mining towns. Being unable to bear proudly this staff of manliness was a source of great shame and a cause for further humiliation for young John. Setting aside the pickaxe, John attempted to handpick slate from coal to bring home a meager week’s wages of $1.50, but he was unable even to perform this task. Thus, John’s malformed foot and poor health ultimately excluded John from the ranks of the miners of Mackeysburg.

When John was fourteen years of age and it was well established that he was unfit to work in the mines, Michael and Ellen were at a loss as to how their fifth child might best use his gifts. Though it was clear that John was determined, witty, faithful, and humble from a young age, it remained unclear how an unlearned man of less than average means could make a living in a mining town if not by the very work sustaining the local economy. Interestingly, however, John developed an interest in shoemaking and desired to place himself under the tutelage of the village cobbler. The humility with which John, “a real foot-sufferer,” admitted his unfitness for the mines allowed one door to close, that God might lead him through others.

As a shoemaker’s apprentice throughout the 1860s, John’s personal struggles met and were shaken by the strife of his homeland. With the leadup to the Civil War and its ultimate ensuing with the Battle of Fort Sumter on 12 April 1861, Abraham Lincoln was the newly inaugurated sixteenth president of the United States and firmly opposed the Confederacy. Though “news traveled slowly in those days, “word of bloodshed and a call to arms soon reached the O’Neills’ small mining town. The miners of Mackeysburg were quick to supply troops for battle, and this put pressure on the village cobbler and his apprentice, young John O’Neill, to produce an abundance of “strong new shoes.” Amid the trials of his country, his town, and the ultimate closing of the village cobbler’s shop, John O’Neill—hardly fourteen years of age—”felt a special call to serve God in the religious state.” This sense of a calling to the religious life deepened in John as he labored throughout his teenage years and early twenties. About 1860, John set off—cobbler tools in hand—on a great journey in which to discern where God might be leading him. John spent the early days of his journeys working for parishes, where he remained for as long as his services were needed. This new itinerant ministry of John’s—which was undoubtedly a cause for further suffering on account of his foot condition—proved rather successful. The demand for itinerant cobblers was high in the days of a sparsely settled America, wherein the nearest neighbor might have been several miles away. John’s business at local parishes also provided the young cobbler with a much-desired occasion for private prayer before the Blessed Sacrament.

Circa 1869, at about twenty years of age, John wandered—”guided, he believed, by the direction of the Blessed Virgin”—out of Pennsylvania and into the west. John partnered with shoemaker Ted Mangan and set off for Denver, Colorado; yet before they arrived, they stopped for a few-days’ respite in St. Louis, Missouri. After John rested his crippled feet, he and Ted trekked on to Colorado, where they finally arrived and soon after parted ways. John had a fruitful career in Denver, where he attended the 6 am daily Mass prior to work. Reflecting on his Rocky Mountain days, O’Neill said the following: “in those days, one who [went to Mass everyday] was counted very pious. I was the only layman that you could find in the church.” Although rare for an individual to receive frequent—let alone daily—Communion in the 1860s, for John this was a vital part of his day; and on Sundays, when resting from a long week’s work, the young cobbler sat for hours praying in the church.

After his stay in Denver, John set off for America’s western limits and arrived in California between the years 1870 and 1873. This leg of O’Neill’s journey “was made on foot…alone,” and “on the way to San Francisco, [John] stopped…here and there to cover his travel expenses, by practicing his trade.” While in California John applied to join a religious community, but he was not admitted to the order on account of his foot condition. Yet, just as John was rejected from the ranks of the miners of Mackeysburg and was not deterred, so too was he not discouraged by this more recent rejection.

Remaining confident in the call he had heard since his fourteenth year, John recalled learning of the Congregation of Holy Cross from another itinerant cobbler, Johnnie O’Brien, who encountered Holy Cross during his time as an apprentice in the shoemaker shop of the Manual Labor School at Notre Dame. The stories John had heard from O’Brien about Notre Dame’s working brothers teaching “blacksmithing, tailoring, carpentering and many other trades” led John to consider that perhaps his vocation might involve joining this “great band of men.” At around the time of Michael O’Neill’s death in Mackeysburg in 1873, John grew “dissatisfied” with the Sunshine State and wrote to the novice master at Notre Dame, Father Augustin Louage, CSC, “to find out if [Holy Cross] was the community he had been seeking for such a long time.”

After meeting with Father Louage and Father Edward Sorin, John O’Neill joined the Congregation of Holy Cross on 9 July 1874. On 8 September of that same year, John entered the novitiate on the grounds of the University of Notre Dame—where John first donned the religious brothers’ habit and took the name Columba. The perseverance that allowed the Irish Saint Columba to lead countless Irish men and women to Christ became a model for Brother Columba’s religious life. With the strength of the faith of his ancestors, Brother Columba—who was, as evinced by provincial Father Charles O’Donnell’s eulogy, “a miraculous man cut from an apparently un-miraculous cloth, he would lead thousands of individuals to experience intimately the healing love of “these Two Hearts: The Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary.”

On 15 August 1876, Brother Columba took final vows in Holy Cross, which included the fourth vow of mission, whereby the religious would vow “to go anywhere in the world the Superior General pleases to send me.” Brother Columba “had finally attained the greatest desire of his heart. He immediately volunteered to go to India and also to Molokai to help Father Damien in the magnificent work among the lepers.” Instead, on 13 September 1876, Columba was assigned to Saint Joseph’s Orphan Asylum in Lafayette, Indiana.

While at Lafayette, Columba “used Lourdes water on the sick boys and says that he had some cures. During the winter of his last year in Lafayette, he nursed a number of boys with the flu.” Brother Columba took no credit for a single cure. Rather, Columba claimed that the cures were the effect of his intercession to the Sacred Heart of Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Brother Columba requested to leave the asylum because there was no longer any need for his trade because, as he writes, “the boys have their shoes.”

By the Summer of 1885, Brother Columba returned to Notre Dame and was assigned to the campus shoe shop, where he remained until his death on 23 November 1923. On the one hand, not much happened during this thirty-eight-year span at Notre Dame: a brother living a simple life, praying in secret, making and repairing shoes. He seldom stepped foot outside of Notre Dame, except for occasional visits to his sister Eliza’s parish, St. Mary’s in Keokuk, IA. On the other hand, Columba’s healing ministry spread far beyond the bounds of Notre Dame’s campus—from the Sacred Heart of Jesus at the center of campus, to Mary’s Immaculate Heart atop the golden dome, and out to the rest of the world.

A decisive moment in Brother Columba’s healing ministry occurred around the year 1890, when Brother Columba began producing and distributing images of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (approx., 10,000 paper badges) and the Sacred Heart of Jesus (approx., 30,000 cloth badges). The brother’s other obligations did not come to a halt, and his devotions were by no means offered at the expense of his other duties. He also saw hundreds of persons in his campus shoe shop, and wrote literally thousands of letters to those who wrote to him of their physical sufferings and requests for prayers and “favors” through his intercession to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

In the early 1890s, Brother Columba also assumed the responsibility of personal caretaker of superior general Father Edward Sorin. This post lasted from 1891 until Sorin’s death on 31 October 1893. Columba’s devotion to the two hearts of Jesus and Mary not only coincided with the brother’s looking after Sorin during the emeritus president’s final days, but it also inspired Columba’s work with the Blessed Mother’s consolation and her Son’s healing mercy. All the while, Columba upheld an attitude of prayerfulness, humility, cheerfulness, and hope in the promise of eternity that awaits us beyond our suffering.

Shortly after Sorin’s death, the Rev. Provincial William Corby, CSC, ordered Brother Columba to return full time to the cobbler shop. This re-assignment to full time ministry as a cobbler inaugurated Columba into a season in which to live the command of ora et labora—or, as Mother Teresa would later say, “Pray the work!”—and be present in a more intentional manner with the students at Notre Dame and the faithful beyond the campus and across the country.

There are over 10,000 letters written to Brother Columba preserved in the archives of the Midwest Province of Brothers, Congregation of Holy Cross. Among these letters, about 1,400 or so, are those written to Columba attesting to “favor” or “cures” received through his prayers to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Also preserved in the archives are about 150 letters and documents written by Brother Columba in which the brother “described his vocation”.

This vocation can be summed up in St. Francis Assisi’s answer to his friars when asked about their vocations: “To lift up peoples’ hearts and give them reasons for spiritual joy.” In summary, Brother Columba intercedes through the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and he expects cures because of his “child-like faith.” Brother Columba is constantly praying novenas and other prayers and expects it from those he helps and from doctors too. Brother Columba relieves the spiritual ills of those not practicing their faith. Brother Columba does not seek notoriety and is surprised when he gets it. Brother Columba has complete confidence in the Sacred Heart, and his life is emblematic of the simplicity of holy men and women like St. Francis of Assisi, St. André Bessette and St. Teresa of Calcutta. The following is a description of Brother Columba’s last days by Brother Isidore Alderton, his superior and a fitting conclusion to his short biography.

“I feel it my duty to write you of the last hours of our Saintly Brother Columba and of the events of the past two days. I shall make no attempt to keep this in order. It will be but a number of statements just as the thoughts come to me. His was a peaceful death. Our men had taken turns watching with him for a number of nights. As I went there day after day it was easily seen that he was gradually going. The last three days he went very fast. Father Gallagher brought him Communion Tuesday morning and was standing over him with the Host raised on high when he passed away. His lips were too tightly closed to give him Communion. He was conscious up to the very last, never complained, never asked for anything except just what was necessary. News of his death soon spread to the people of South Bend and vicinity and dozens of the members of the Community, Sisters and strangers were there to view the body before it was even in the casket. For the past two days and nights the parlor in the Community House has been a veritable shrine. He looked so peaceful, so happy it was difficult to say prayers for him and I am convinced that thousands of petitions were made to him where but hundreds were said for him. The members of the Community were all there, the Sisters from St. Mary’s, from the kitchen, the hospital, the schools. All who were able to walk or to ride were at his bier. The professors from the college, students and strangers all made their pilgrimage. One had to wait in line for his turn to enter the room or get near the remains. They came with their beads, their badges, their medals, cards, and trinkets and all were applied to his hands and face. The high and the low, the rich and the poor, the learned and the unlearned all became as little children in his presence. Not one entered and left without carrying some precious article that had for him become a real treasure because it had touched the body of one of the holy ones of God. I have talked with a number of the members of the Community this afternoon and all express the same sentiment: “It all seems like a dream, a part of the ages that we felt was in the dim past.” They did not stop with this. They came with handkerchiefs, yards of cloth and ribbon. We sent to Chicago and purchased all the Sacred Heart badges in the City and yards upon yards of goods. Three of us stood there for over a half-hour applying the badges a dozen at a time. These will be kept to be given to the members of the Community. I am enclosing a number of badges for the members of the house-own personal use. I placed the names of the same and applied personally—each one separately in the name of the person whose name was on the badge and at the same time I prayed that our good Brother might obtain the graces or blessings the wearer might request. What can be said of the funeral? It was a Community funeral, as grand as could be arranged with visitors from the vicinity and even from distant parts. I will not speak of the sermon of Father provincial. It will have to [be] read in order to be appreciated fully. I shall send a copy of this as soon as it appears in print. The casket was opened at the grave that other friends might view the remains and one [sic] more the procession came. Old and young, rich and poor they came forward and placed their articles on his body and these same articles became relics to be handed down from generation to generation. You may call it sentiment or whatever you like but could you have witnessed that sight I am sure the memory of it would remain fresh until the end of your days. To see such men as Father Bolger, Father Haggerty and Father Hugh O’Donnell go forward and place their beads upon his withered hands would convince a man that there was something beyond the power of men to describe. Members from Moreau, the Seminary, Novitiate and Dujarié they all have their treasures today and all have others to send to their parents. The world and the strangers were anxious to hear about the miracles but it seems to be that the members of the Community thought little of these things during these days. They meditated on his life, taking into account the sacrifices he made, his example of humility, love of neighbor, confidence in God, lively faith, devotion to the Sacred Heart, life of prayer, of poverty, etc. etc. and all realized that in these was found the secret of his sanctity. His remains have been conveyed to the earth but there is no question but what his work will continue. If in his lifetime he was powerful in obtaining assistance for us what can be said of his power tonight when he is resting close to the Sacred Heart of our Divine Lord? He spent his life promoting this devotion to the Sacred Heart, the Sacred Heart has surely been very good to us as a Community and as individual members and it now remains for us to but increase that devotion in ourselves and spread the same to those in our charge. Let us not forget to thank Almighty God for having given us such a member as Brother Columba: What an honor for our Community to produce such a saintly character…what an honor for each of us to belong to a Community that is capable of producing such members. Many orders much larger than ours cannot boast such. Why is it all? The answer is found in the text of the sermon: “Learn of Me because I am meek and humble of heart.” We may never be able to perform the wonderful cures attributed to him but all that amounts to but little. He is enjoying the Beatific Vision this night because he was a faithful member of Holy Cross. Each one of us will have the same opportunity. Let us follow his example.”

Submitted by Mr. Edwin Donnelly, CSC, and Brother Philip R. Smith, CSC.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.