August 3, 2021 // Bishop

Mass reunites Fort Wayne Pedro Pan refugees

As protests took place in Cuba against the communist government in power, a group of refugees who fled the country after Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution gathered in Fort Wayne July 24-25 to commemorate the 60 years since they came to the area.

Sent to the U.S. as teenagers by their concerned parents, these now-grown men were part of an effort called Operation Pedro Pan. Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades presided at a Mass for a reunion of the group at the St. Mother Theodore Guérin Chapel in downtown Fort Wayne July 24.

The Pedro Pan program began when Msgr. Bryan Wash, a priest of the Diocese of St. Augustine, Florida, foresaw an overwhelming influx of unaccompanied immigrant children from the island nation of Cuba to Miami in 1960. Through the operation, parents who feared termination of their parental rights and communist indoctrination of their children realized there might be a way to protect them.

The Catholic Welfare Bureau that Father Walsh headed, worked with the federal government and other organizations to airlift the children from Cuba to Miami and find places throughout the country for them to live. The airlift portion lasted a year, from 1961 to 1962, when air travel was restricted due to the Cuban Missile Crisis. More than 14,000 youths escaped Cuba through Pedro Pan.

Photos provided by Mark Mosrie

Former Pedro Pan refugees who were relocated to Fort Wayne celebrated Mass with Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades July 24 at the St. Mother Theodore Guerin Chapel. From left are Julio C. Garcia, Michael Barnet, César de la Guardia, Nelson Ayala, Bishop Rhoades, Reinaldo Alfonso, José Raymundo López, Alexander Müller and Pedro Ledo. Pedro Pan, or “Peter Pan,” was the name of an early-1960s effort to protect teenage boys from communist indoctrination and conscription by bringing them, unaccompanied, to the U.S.

Originally, three separate groups of boys arrived in Fort Wayne in 1961, with an additional two groups in 1963 and a final group in the summer of 1964. The young men who came were first housed at St. Vincent Villa, a former orphanage operated by the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend. Religious sisters ran St. Vincent Villa and provided care for the boys, while lay Catholics from local parishes served as their guardians and foster families and spent time with the boys on the weekends. Most of the boys attended Central Catholic High School, and some were able to reunite in Fort Wayne with parents who managed to leave Cuba and start new lives.

Michael Barnet, a member of the first group to arrive, is considered the Pedro Pans’ historian. He stated that: “The purpose of the reunion was mainly to celebrate our coming to Fort Wayne and also to thank the people of Fort Wayne for welcoming and allowing us kids to start a new life here, thus making the U.S.A. our ‘home away from home.’”

The Operation Pedro Pan organization’s banner represents more than 14,000 children who were airlifted from Cuba to the U.S. after Castro’s 1959 revolution due to parental fears about the new regime. — Photos by Jennifer Barton

Of the 41 boys who came to the area, some have moved away or passed on; but others continue to call Fort Wayne their home. By and large, they have found success in careers and family life through the opportunities offered in the United States. Many of them still fondly remember Msgr. William Lester, who led the program with cheerful dedication to their welfare.

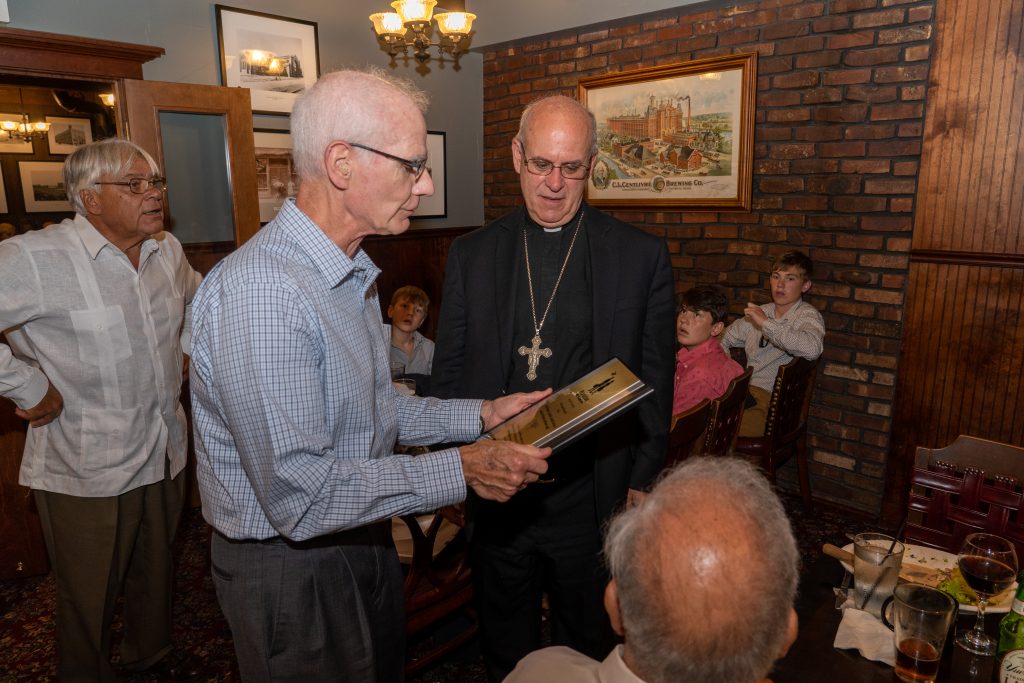

During the reunion, group members presented Fort Wayne Mayor Tom Henry with a plaque expressing their gratitude to the people of the city. Bishop Rhoades was also presented with a plaque thanking the Catholic Church and its members who were instrumental in helping the Pedro Pan boys start new lives.

Around 35 Pedro Pans and spouses attended the Mass and dinner with Bishop Rhoades on Saturday evening. They took time to visit the old St. Vincent Villa and basked in the camaraderie that is born from shared experiences.

Alejandro Muller said that “when we see each other … it’s like we haven’t missed a beat. It’s fun, we can kid around like we did 60 years ago.”

Muller lives in O’Fallon, Missouri, but Fort Wayne will always be a second home to him, he said. He still knows his way around town. He came over as a 15-year-old boy, completed high school at Central Catholic and met his wife of 56 years at St. Joseph Hospital.

He recalled that only three of the people he had known in Cuba did not support Castro, prior to the revolution. One was a priest at the Jesuit school that Muller attended – the same one Castro had attended previously. But by the summer of 1959 anti-Castro sentiments had begun to grow, and Muller became involved in underground work to overthrow him — mostly through writing and spreading materials around Havana.

Muller was captured, imprisoned. The faith he learned from his father and the Jesuit school helped see him through tough interrogations. A couple of weeks after his capture, however, he and the men who had been arrested with him found themselves alone in the university that served as their jail.

Freed, Muller returned home to resume his life. Three months later, he found himself on a flight bound for Miami carrying only a physics book. When he arrived in Miami, he knelt and kissed the ground.

Using the education he received at Central Catholic, Ivy Tech and Purdue University, Muller built a career and has 10 patents to his credit. His two sons have served in the U.S. military with distinction, and he has retired to a comfortable life.

Several of the Pedro Pans have chosen not to return to Cuba, because the political situation that they fled exists to this day. The men share the sentiment that one of them, Reinaldo “Camagüey” Alfonso wrote about in an account of his story: that he “will not visit or live in a communist country.”

Several of the Pedro Pans have chosen not to return to Cuba, because the political situation that they fled exists to this day. The men share the sentiment that one of them, Reinaldo “Camagüey” Alfonso wrote about in an account of his story: that he “will not visit or live in a communist country.”

Like Alfonso, Muller has not been back to Cuba, though he has watched footage and recognized the ruins of places he once knew. And while coming to Fort Wayne was a tremendous adjustment for him, as it was for all the young men, he chooses not to speculate on what-ifs. “I love the life I have here; I love my wife and kids,” he said. “I can’t imagine it would have been any better if I’d stayed in Cuba.”

Gratitude and patriotism flow deep in the veins of the Fort Wayne Pedro Pans. “I am forever so thankful to the United States,” Muller said. “I get really upset when I see people put down the U.S., when they disrespect the flag.”

After traveling to numerous locations in Germany, England, New Zealand and other countries, he has yet to find a place that compares with what he’s found in America.

“There’s no place like the U.S. It hurts me to see people find fault with it.”

One of the last of the Pedro Pans to come to Fort Wayne, Julio Garcia’s experience was a bit different from some of the older boys. Because he bounced between foster homes and children’s homes in Miami for around three years, Garcia had a better grasp of English than many of the others.

By the time he arrived in Fort Wayne, the boys were living in a house on Wayne Street. At age 16, he was one of the youngest in the house, and he recalled that they were a “rowdy bunch.”

The refugees and the families they developed formed a close community in town in the ‘60s, and Garcia still remains friends with Pedro Ledo, Jr., one of the original Pedro Pans. He enjoyed reuniting with them, saying, “I got to see some of the older guys that I haven’t seen for some time.”

Of his experiences, Garcia reflected, “Growing up in foster homes and children’s homes was quite a struggle, but I eventually made it to Fort Wayne and made my home here.” He met his future wife of 50 years at Central Catholic, converted to Catholicism and became a part of St. Vincent de Paul Parish, raising eight children and teaching in the public schools.

In his homily at Mass, Bishop Rhoades pondered the hardships the men must have experienced 60 years ago, alone in a foreign land and separated from their families. He paid homage to the families who made the sacrifice of sending their children to the U.S. in hopes of a better life. He also gave credit to the local Catholic priests and laity who supported them in their new home.

He remarked, “Only the Lord knows what would have happened if you would have remained in Cuba 60 years ago. In God’s providence, you came here. You were able to build a new life here and to discern your vocation in life. … The Lord has sustained you with His love and grace.”

He reflected on the Biblical accounts of the many times God physically fed His people, from the manna in the desert to the multiplication of the loaves and fishes in the day’s reading from the Gospel of John.

“These miracles testify to God’s compassion for us. He wants to satisfy our hungers, not just our physical hungers, but all the hungers of the human heart: the hunger for peace, for justice, for truth, for freedom, for love,” he said.

“Only God can satisfy our deepest hungers. Jesus came as the Bread of Life. He alone satisfies the hungers of our hearts.”

Bishop Rhoades called for unity with those still struggling for freedom and better lives in Cuba. “We can be in solidarity with the Cuban people through our prayers for peace and reconciliation and, of course, for freedom. We ask Jesus, the Bread of Life, to satisfy the hungers of the people of Cuba. And we ask for the intercession of our Lady of Charity, ‘Nuestra Señora de Caridad de Cobre,’ for the people of Cuba.”

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.