September 14, 2021 // Bishop

Mass, museum exhibits to recall 175th anniversary of Miami Tribe’s removal

A Mass next month and two museum exhibits will remember the 175th anniversary of some members of the Miami Tribe of Native Americans being forced to leave their homeland in Indiana to move to a reservation in what later became the state of Kansas.

Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades will observe the Miami’s removal, which began Oct. 6, 1846, during the 5 p.m. Mass Oct. 2 at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Fort Wayne. The exhibits will take place at the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend’s Diocesan Museum on the Cathedral grounds and at the Whitley County Historical Museum in Columbia City.

Photos by Kevin Kilbane

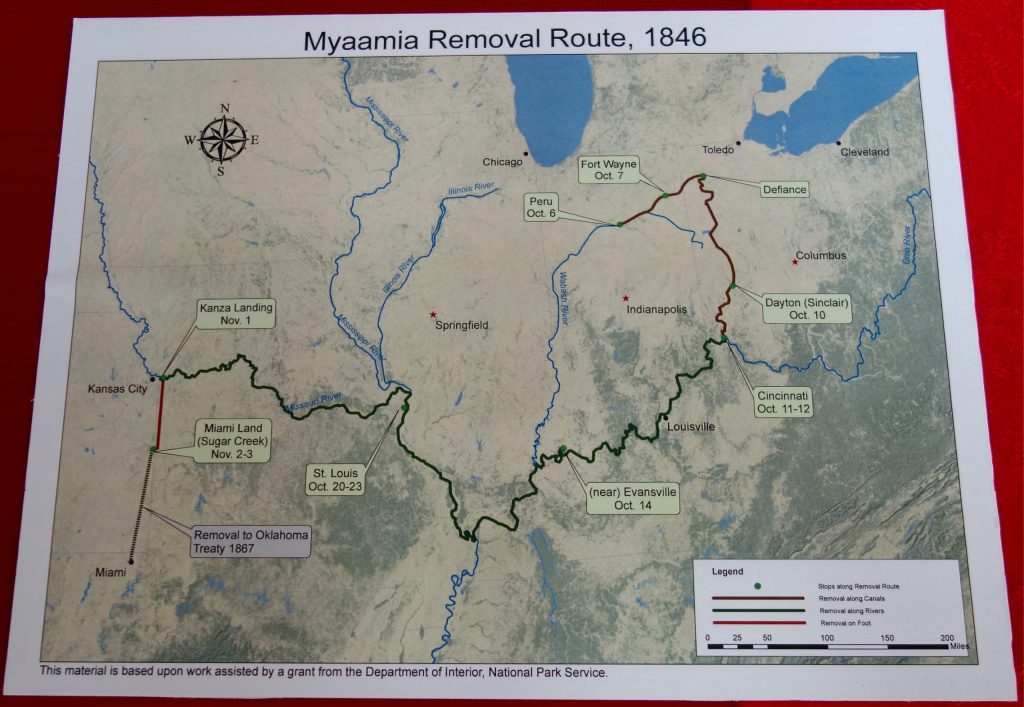

This photo shows a map of the route used in 1846 to forcibly move Miami people from their homeland in Indiana to new land in what became eastern Kansas. A Mass will be celebrated by Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades Oct. 2 in remembrance of the Miamis’ traumatic removal.

Forced west

The Miami people, who are called “Myaamia” in their own language, have lived in what is now Northern Indiana since long before Fort Wayne-South Bend was created as a diocese by the Church in 1857.

French fur trappers and traders found the Miamis to be present when they began arriving in the Fort Wayne area in the middle to late 1600s. French missionaries then began sharing the Catholic faith with the Miamis and other Great Lakes tribes.

“They introduced us to Jesus,” said Dani Tippmann, a Miami Tribe member who is a member of St. Patrick Parish in Arcola. Many Miamis became Catholic and sent their children to Catholic schools.

The French missionaries also wrote down detailed descriptions of Miami life and culture, said Tippmann, the director of the Whitley County Historical Museum. Today, translations of those writings aid Miami people in recovering their culture.

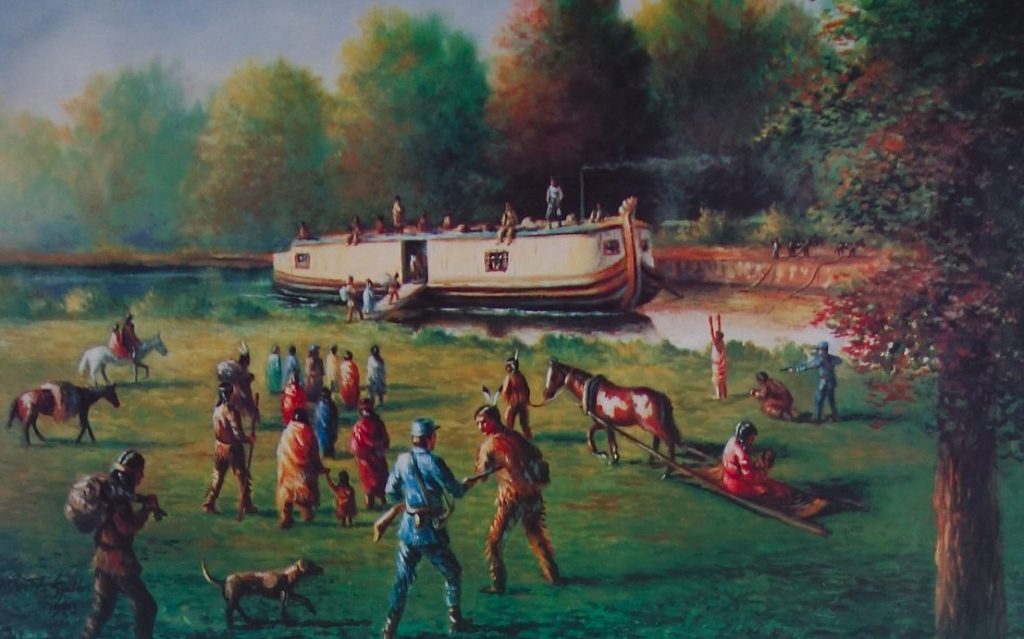

Miami Tribe members are forced onto canal boats for relocation to the West in this painting that will be part of the “Our Forced Removal” exhibit opening Oct. 6 at the Whitley County Historical Museum in Columbia City.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 launched the U.S. government’s efforts to move Native American tribes from their homelands in the eastern United States to land west of the Mississippi River. Treaties signed by the Miamis relinquished land to the American government and included a provision that about half of the 600 Miamis in Indiana would move to land in what became eastern Kansas, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma said on its website, www.miamination.com.

The Miamis delayed their removal. This prompted the U.S. government to send a small Army force to make them move west in early October 1846, according to Diane Hunter, tribal historic preservation officer for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. She wrote about the delay in the Sept. 3 post “A Small Military Force, 1846” on the Miami Tribe’s Removal Commemoration blog, aacimotaatiiyankwi.org/myaamia-history/removal-commemoration.

French-born priest Father Julian Benoit, who was assigned in 1840 to serve the Fort Wayne area and became a trusted friend to the Miamis, was among local leaders who objected to use of military force against them, Hunter wrote in her post.

The Miamis had to board canal boats for travel to Cincinnati, where they changed to a steamship for river travel to the Kansas City area. They then traveled overland about 50 miles south, arriving in early November at their new land at Sugar Creek.

Seven died along the way, Tippmann said, and about 10 percent of those who survived the trip died before the end of the year. About 20 years later, the tribe then had to move again to their current reservation in Oklahoma.

The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma now has more than 6,000 members, including about 820 in Indiana and 260 in Allen County, Hunter said.

“I think we still are feeling the effects of it,” Tippmann said of the 1846 removal. “So much changed so quickly. We were separated from loved ones. We were separated from neighbors. This area is the dust of the bones of our ancestors.”

The Miamis who were allowed to stay bore the guilt of seeing family and friends forced to move away, she added.

She has found comfort through the Catholic faith. “Catholic people’s hearts are open to understanding what our people went through, and they are willing to step beside us and help us go through it,” she said. “It makes everything so much easier.”

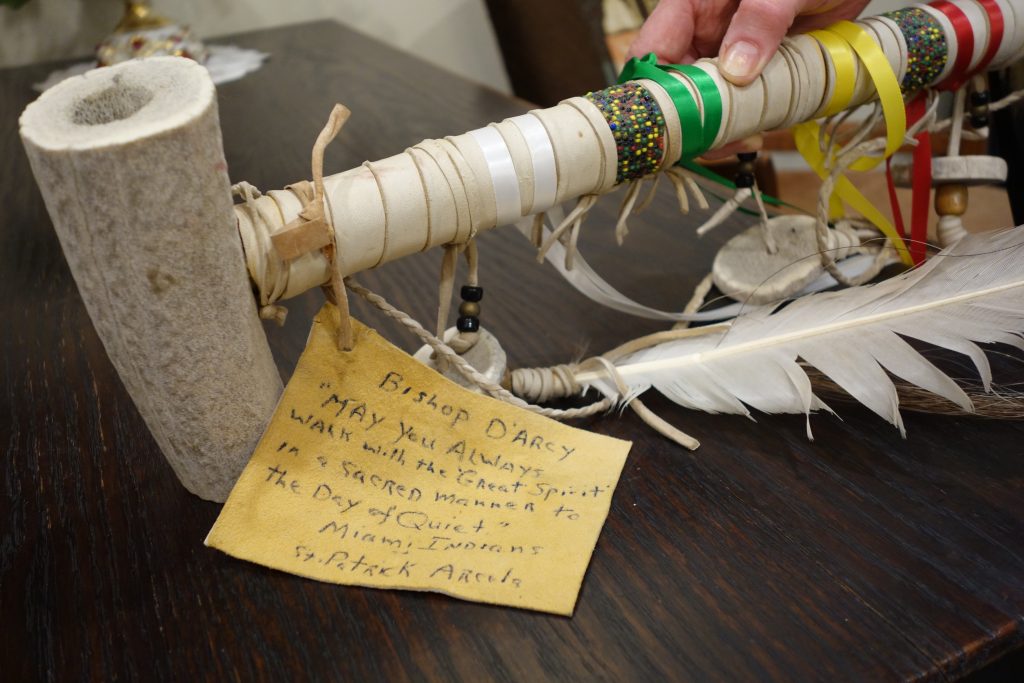

An elk antler pipe given by Miamis of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend to Bishop John M. D’Arcy will be among the items displayed in a Diocesan Museum exhibit commemorating the 175th anniversary of the Miami Tribe’s forced removal in 1846 to land in what became Kansas.

Diocesan Museum

The diocese’s museum, 1103 S. Calhoun St. in Fort Wayne, will present its exhibit on the Miami removal Oct. 1-30. Museum hours are 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Tuesdays-Saturdays and by appointment. Admission is free, as is parking in the cathedral lot.

Exhibit highlights include the desk of Father Benoit, who wrote frequently about the Miamis to Church officials and others, and a biography booklet on Father Benoit that was published in 1885, the year he died. The exhibit also will include an elk antler pipe local Miamis gave to Bishop John M. D’Arcy.

The exhibit allows the diocese to acknowledge the Miami removal anniversary in a more extended way than the Oct. 2 Mass, museum Director Kathryn Imler said. With the museum now located on Cathedral Square, she also believes it is important to honor the Miamis’ connection to that land because it holds spiritual significance for them and formerly contained a cemetery where they buried their dead.

Father Julian Benoit was a friend and adviser to the Miamis. His desk will be part of the Diocesan Museum exhibit. He opposed the use of military force to remove them in 1846 to land in what became Kansas.

Imler hopes the removal exhibit will be a step toward developing a larger display about the history of Native Americans and the diocese. The Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend is the only one in Indiana where two sovereign Native American nations — the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi — own property and have an official tribal presence.

Whitley County exhibit

The “Our Forced Removal” exhibit will have its grand opening at 3 p.m. Oct. 6 at the museum, 108 W. Jefferson St. in Columbia City. An accompanying lecture series will explore the Miamis’ removal and their culture. A rotating display of work by Miami artists also will be presented during coming months.

Museum hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays-Thursdays and 9 a.m. to noon Fridays. Admission is free.

“We are looking to tell the story of the Miami people, focused on removal,” museum Director Tippmann said. The museum’s displays, which will be up through mid-September 2022, will feature donations from the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, including a wigwam, interactive stations featuring maps and language concepts, and a slide show on the history of Native American tribes in Indiana.

This dugout canoe will be cleaned out for use in the “Our Forced Removal” exhibit at the Whitley County Historical Museum in Columbia City.

Children can crawl into and sit in the wigwam and possibly sit in a dugout canoe, Tippmann said. Visitors can try creating patterns using Miami ribbon work and learn about treaties between the Miamis and U.S. government.

Tippmann also plans to honor Miamis who died during the removal and soon after arriving in what is now Kansas.

“We want to memorialize those people and talk about all the people who were made to leave,” she said.

The lecture series schedule consists of:

4 p.m. Oct. 6: Diane Hunter, tribal historic preservation officer for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, “Miami People: A Living People with a Past.”

4 p.m. Oct. 13: George Ironstrack, assistant director of the Myaamia Center at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, “Picking up the Threads of our Knowledge: The Impact of Forced Removal on the Revitalization of Myaamia Language and Culture.”

1 p.m. Oct. 16: Katrina Mitten, a Miami tribe member and noted artist, “Art and Assimilation: The Effect of Removal on Those Allowed to Remain.”

4 p.m. Nov. 3: Todd Maxwell Pelfrey, executive director of The History Center in Fort Wayne, “Mainsprings of the Wildcat: The Making of Chief Jean Baptiste de Richardville.”

4 p.m. Nov. 17: Doug Peconge, community programming manager for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, “Myaamia Lacrosse.”

4 p.m. Nov. 24, Dani Tippmann, a Miami member and the museum’s director, “Myaamia Plant Traditions.”

A kettle once was used by Kiilhsookwa, also known as Kil-So-Quah, the granddaughter of Miami Chief Little Turtle, will be among Miami items displayed at the Whitley County Historical Museum exhibit.

The museum hopes to present a livestream of the lectures for people who aren’t able to attend. If coronavirus levels prevent in-person presentations, the museum plans to present the speakers on the Zoom videoconferencing system. For the latest updates, check the museum’s website, www.whitleymuseum.com, and its Facebook page.

Lasting effect

The directors of the Whitley County and Diocesan museums hope their exhibits have impact beyond recognizing the 175th anniversary of the Miamis’ removal.

Imler sees strong parallels between what the Miamis experienced in 1846 and what refugees and immigrants face today. She’d like visitors to think about the Miami removal and become more open to people from another background and try to see things from the other person’s point of view.

“Even though we are focused on history, there is a human side to it, too,” Tippmann said. Remembering that can help people do better in the future, she added.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.