November 5, 2019 // Diocese

Faith endures for black Catholics

They came to northern Indiana seeking equal treatment and better job opportunities. They didn’t always find it.

The story of black Catholics in the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend is one of faith, hope and perseverance. The diocese and the Catholic Church in the U.S. recognize that heritage in November during Black Catholic History Month.

Blacks have lived in the diocese since before the northern half of Indiana was designated the Diocese of Fort Wayne in 1857. History books record African Americans working as slaves in the early 1800s in Fort Wayne.

The earliest documented free person of color to settle in Fort Wayne was Bert Reid, who arrived in 1827, said Roberta Ridley, chairman of the African American Genealogical Society of Fort Wayne. Reid, a Revolutionary War veteran, worked as a town crier and handyman.

African Americans continued trickling into what is now the diocese throughout the 1800s. The movement became a flood from 1910 to 1970 during the Great Migration, when several million blacks fled racial segregation and economic repression in the South to seek fair treatment and jobs in the North, the U.S. Bureau of the Census reported. Many found work in Midwest manufacturing centers such as Fort Wayne, South Bend, Chicago and Detroit.

In Fort Wayne, census records show the black community grew from 572 people in 1910 to 18,921 in 1970, jumping from 0.9% of the city’s population to 10.6%. In South Bend, the number of blacks climbed from 604 in 1910 to 17,737 in 1970, soaring from 1.1% of the city’s population to 14.1%.

Blacks now make up about 15% of the population in Fort Wayne and about 26% in South Bend, based on 2018 Census Bureau estimates.

In the early 1900s, several black Catholic families who settled in South Bend reportedly found that some white Catholics didn’t follow Jesus’ urging to love thy neighbor. However, a pastor offered a hall for the families to meet for Mass, and that ministry led to the creation of St. Augustine Parish in 1928 to serve blacks in the city.

“Pastors and lay leaders did significant outreach and relationship building with the surrounding African American community — Catholic and otherwise — and took risks to fight for our issues: fighting for civil rights, against racism, to strengthen families, for quality education, for fair housing, for better health care and for socioeconomic justice,” said Deacon Mel Tardy of St. Augustine.

In Fort Wayne, black Catholic families found homes at St. Mary, Mother of God, St. Patrick and St. Peter parishes. Some non-Catholic black families also converted to Catholicism after enrolling their children in Catholic schools and developing a desire to join the Church, he said.

The assassination of civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968 brought more change.

Worried that black Catholics might leave the Church, diocesan leaders founded the Office of Black Catholic Ministry to reach out to them, said the Father Theodore Parker, who then was a deacon at St. Mary Parish in Fort Wayne and part of the Black Catholic Ministry team. He now is pastor of St. Charles Lwanga Catholic Church in Detroit.

Father Parker said the Black Catholic Ministry office worked mostly with blacks who were attending St. Mary in Fort Wayne and St. Augustine in South Bend.

Black Catholics in the diocese also connected with the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus after its launch in 1968.

Locals wanted to know more about other black Catholics and what was happening in other states, recalled Metrice Smith, a current St. Mary member. At the caucus’ national conventions, they enjoyed networking with other black Catholics and worshiping together.

“It was a time in the Church when everything seemed possible,” Father Parker said.

At St. Augustine, for example, parish members began incorporating gospel music and other aspects of their culture into worship services, Deacon Tardy noted.

Although the Office of Black Catholic Ministry closed some years ago, the Black Catholic Advisory Board was created in 2012 to advise the diocese on evangelization and pastoral care of people of African descent.

Today, the diocese has no predominantly African American parishes.

With greater freedom in where people live and what parish they attend, more black Catholics may join a parish close to home or where their children attend school, Deacon Tardy said. Indiana’s School Choice voucher program makes Catholic schools more accessible for black and other families.

Some black Catholics also may have stopped going to Mass or may go to non-Catholic churches that serve more people of color or seem more welcoming and culturally sensitive, he surmised, but added that black Catholic young people express strong interest in learning how to live as a Catholic.

“Welcoming folks is not enough,” he said. “Good catechesis teaches them how to walk with Christ when, as one St. A’s song goes, ‘the storms of life are raging.’”

In the past 25 years, immigrants and refugees from Africa, Haiti and other countries also have settled in the diocese. They bring new experiences, perspectives and gifts to the diocesan family.

With such a diverse community of Catholics of African descent, Deacon Tardy said, “we must develop better intercultural competence skills for Catholic schools, parishes and institutions if we are to truly welcome and affirm one and all who come to the Catholic Church of the 21st century.”

Lasting faith

Two families’ ancestors were baptized Catholic as slaves. Another family became Catholic thanks to a friendly priest who walked regularly in their neighborhood and stopped to chat with residents.

The stories of the Summers, Mudd and Smith families illustrate the range of experiences among African American Catholics in the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend.

Provided by Wendy Summers

Wendy Summers of St. Pius X Parish in Granger has found her Catholic faith goes back, on her father’s side of the family, to Millicent McAlpin, above, born a slave in 1865 in Louisiana.

Louisiana roots

Wendy Summers’ Catholic roots go back, way back.

Two enslaved Africans on her maternal grandmother’s side of the family apparently were baptized about 1735 as they walked off the ship that hauled them from Africa to a port — likely New Orleans — in what is now the United States.

Summers, a Granger resident and St. Pius X Parish member, traced the Catholic faith on her father’s side of the family to Millicent McAlpin, a woman born a slave in 1865 in Louisiana.

Summers, 65, also is related to Venerable Henriette Delille-Sarpy, a candidate for sainthood. Delille-Sarpy in 1842 co-founded the Sisters of the Holy Family religious order and worked to aid the poor, elderly and slaves in New Orleans.

Between 1919 and 1929, Summers’ father’s family moved from the South to Chicago, where her father was born, as part of the Great Migration, she said. They were among several million blacks who from 1910 to 1970 migrated from the South to the North to escape racism and to find better jobs.

While growing up in Chicago, Summers had many Catholic relatives. Parishes in Chicago were segregated racially, however, so family members attended black parishes.

After she and her husband, James, married in 1975, they experienced the racial prejudice while attending a Catholic church where they lived in Oak Park, Illinois.

“People wouldn’t sit in the pews with us,” she recalled. “They wouldn’t shake hands with us at the sign of peace.”

She began going to Mass at black parishes attended by her grandmothers.

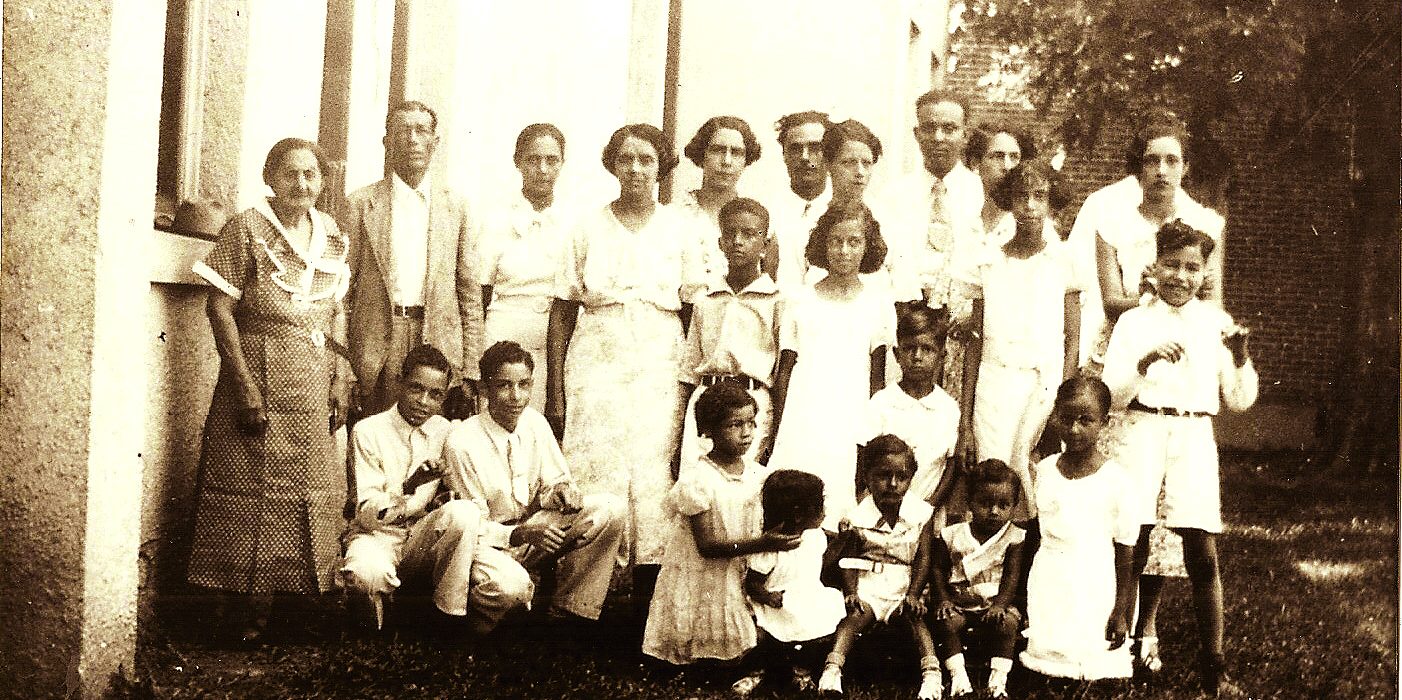

Provided by Wendy Summers

The family of Wendy Summers’ maternal grandmother, Irene LeGras, is shown in 1936, including her parents, their children and grandchildren born by that time. Summers, of St. Pius X Parish in Granger, has traced some of her family’s Catholic heritage to African slaves baptized about 1735.

When Summers and her husband moved to Granger in 1999, they started attending the closest Catholic church, St. Pius X.

“I find the parish to be very welcoming,” she said.

St. Pius X has about a dozen black families among its 10,000 members, however, so they feel a little isolated, said Summers, who is a member of the diocese’s Black Catholic Advisory Board. The board helps the diocese minister to blacks.

Summers and her husband also participate in activities at St. Augustine Parish in South Bend. In recent years, that parish has transitioned from predominantly black to multicultural, but it retains its gospel choir and some African American traditions.

Provided by Adrian Wells

This photo shows Adrian Wells’ relative, Valerie Mudd Williams, right, with her brother, Derrick Cox, a friend and Sister Norbert at the time of Williams’ confirmation at St. Peter Parish in Fort Wayne.

Kentucky legacy

Adrian Wells of Fort Wayne traces the Catholic faith on his mother’s side of the family to a boy born into slavery in 1845 near Calvary, Kentucky, and baptized as a Catholic in 1846.

Most of the Mudd family came from an area north of Calvary near Springfield, Kentucky, including Wells’ great-great grandfather, George Mudd, who fought as a member of the Union Colored Troops in the Civil War. The area was heavily Catholic, and slaves and free people all were baptized Catholic, said Wells, 43, the historian for the African American Genealogical Society of Fort Wayne.

The first members of the Mudd family moved to Fort Wayne in 1918 or 1919, but Wells hasn’t discovered why. His great-grandmother, family matriarch Mary Catherine Mudd, initially attended St. Patrick Parish and later moved to St. Peter Parish, where most of the family attended church and school. Some family members later joined St. Patrick, Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and St. Joseph parishes in Fort Wayne, he said.

Mary Catherine was devout. One family story says if you weren’t at Mass when you were supposed to be she searched for you and made you sit in the front pew, said Wells, who grew up attending Mass but never became Catholic.

Family members participated in all parish activities, such as Rosary Society, Knights of Columbus and special events, Wells said.

Most Mudd family children went to Central Catholic High School until it closed in 1972. They included Calvin “Cal” Mudd, who served as secretary of the senior class of 1937 along with playing football and basketball.

Wells’ late aunt, Corrinne Mudd Brooks, was very active in the church and Fort Wayne community.

Provided by Adrian Wells

The eighth grade confirmation class at St. Peter School in Fort Wayne includes a young Maryolyn Mudd Wells, center, the grandmother of Adrian Wells of Fort Wayne, as well as two young black men. The Mudd family arrived in Fort Wayne about 1918-19.

Close to home

Metrice Smith was 3 years old when her parents moved the family in 1943 to Fort Wayne. They had left Mississippi about a year earlier and lived in Memphis, Tennessee, before settling in Fort Wayne.

“I know my Mom did not like sharecropping. She did not like farming,” Smith, now 78, recalled.

In Fort Wayne, they and their mostly black neighbors bonded as a strong community.

“We were poor, but we were loved and felt safe,” she said of her youth.

In the early 1960s, after growing up and marrying, she and her late husband, Frank, lived near St. Peter Parish in southeast Fort Wayne. They got to know Father Robert Yast, the assistant pastor at St. Peter, as he strolled nearby streets and chatted with neighbors.

The conversations inspired Frank Smith, who didn’t grow up practicing a faith, to want to learn more about the Catholic faith. Metrice, who was raised Baptist and attended that church, hesitated about changing faiths but agreed to go if her husband wanted to attend Mass.

“I believe in family,” she said. “If we are going to go to church, we are going to go as a family.”

She, her husband and their three daughters converted to the Catholicism in 1966. They became one of a few black families at St. Peter at that time, but they felt welcome, she said. The Smiths, whose family grew to four daughters, also sent their children to Catholic schools.

By the late 1970s, they had moved near St. Henry Parish in Fort Wayne and joined there, she said. The closing of the International Harvester factory in Fort Wayne in 1983 led them to relocate to Springfield, Ohio, for her husband’s job.

When they moved back in 1999 to Fort Wayne, Smith said they began attending St. Mary Parish because their daughters had joined there. She still belongs to the parish, though only a few blacks now attend there.

“The people who come there want to be there,” she said, “and they are giving and loving people.”

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.