January 12, 2022 // Diocese

Extending welcome key to boosting African American vocations

They are called vocation stories: people’s accounts of how they felt God calling them to use their faith and gifts in service to the Church, their family or to others. Many people in the Catholic Church have these stories. Others don’t have an ending yet: someone may have felt a call but never received the invitation or encouragement to pursue the vocation God placed on their heart. Too many of those unfinished stories involve African Americans and other people of color.

However, African American leaders in the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend believe the Catholic Church has the means and tools to help more people of all backgrounds complete their vocation story.

“I am very excited about the future,” said Deacon Mel Tardy of South Bend, the only ordained African American clergy member in the diocese. “I have a sense in my heart God already is working on things.”

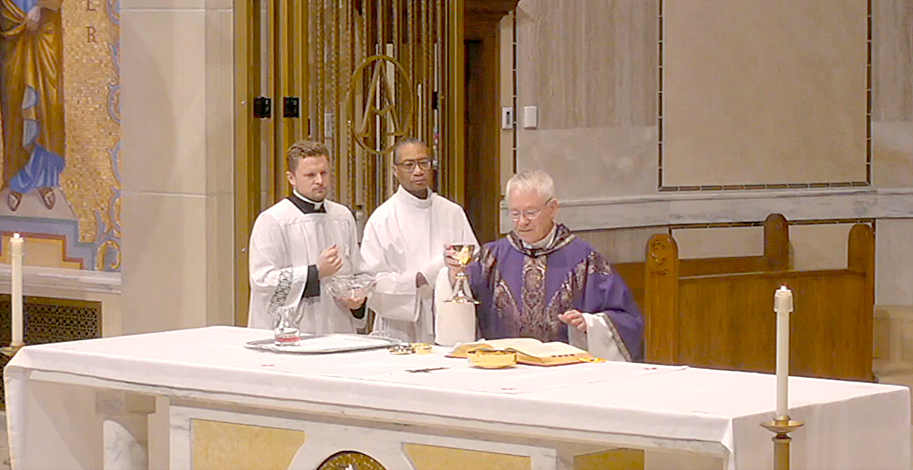

Today’s Catholic archive photo

Deacon candidate James Summers of St. Pius X Parish in Granger believes the Catholic Church’s social teachings can serve as a framework for parishes in becoming more welcoming to Catholics of all backgrounds and to encourage more vocations among African American members. Summers is beginning his fourth and final year of deacon formation on his way to becoming the diocese’s second ordained African American clergy member.

The numbers

Of the approximately 41 million African Americans living in the United States, about 3 million, or 7 percent, are Catholic, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) reports on its website, usccb.org. African American Catholic clergy and religious include one cardinal, four bishops, and about 250 priests, 440 deacons, 400 religious sisters and 50 religious brothers. They represent about .04 percent of the 3 million African American Catholics.

Figures weren’t readily available on the number of African American Catholics in this diocese. Some Catholics may believe the diocese already has plenty of priests from Africa. But African priests’ life experiences differ greatly from those of African Americans growing up with the sometimes-subtle, sometimes-overt racial discrimination in America, Deacon Tardy and James Summers believe. A seventh-generation Catholic, Summers is beginning his final year of formation to become the diocese’s second African American deacon. Summers and other candidates for the diaconate are scheduled to be instituted as acolytes Jan. 16 during a Mass at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Fort Wayne.

All are called

Through baptism, all Catholics are called to a vocation, whether it be single or married; lay person, clergy, religious or consecrated life, said Deacon Tardy, who serves at St. Augustine Parish in South Bend and also chairs the diocese’s Black Catholic Advisory Board. St. Augustine was founded in the early 1900s to serve African American Catholics who weren’t welcome at white parishes and is now home to people from a mix of cultural backgrounds.

Many young people begin discerning God’s call to a vocation by age 12 or 13, Deacon Tardy said. That also is about the age when some people start perceiving African American youths as a threat. The perception can derail attempts to follow a vocation call.

“African Americans have been made to feel like visitors in our own church,” Summers said.

He has witnessed priests hesitate to give Communion to African American Catholics because they didn’t believe African Americans could be Catholic. At a workshop a couple of years ago, a young African American woman recounted how parishioners at a Catholic Church had scrutinized her with the underlying message, “What are you doing here?”

To attract and retain more African American members and to encourage more vocations from that community, Deacon Tardy said the Church must speak out against racism in America and become more welcoming to people of color. In short, Catholics need to love each other better.

“A big part of love is someone is noticed,” he said. “I can’t go past you and not recognize your humanity and that you have a vital role in the kingdom of God. I need you to be who you need to be for me to be who I need to be.”

To show that love, diocesan African American leaders suggest parishes and schools:

— Display images of saints of African descent and African American Church leaders so parishioners and visitors see people who look like them and feel welcome. The Catholic Church currently has no African American saints, but six African Americans are candidates for sainthood.

— Emphasize that God calls everyone to a vocation. Help people recognize their vocation and nurture their efforts to attain it.

— Recognize the gifts and talents God gives each person and encourage individuals to use their gifts.

— Help children receive a good education. Young people need a strong academic foundation to complete seminary studies.

Catholic social teaching, which urges people to love and care for one another, also provides a framework for healing and moving forward together, said Summers, who attends St. Pius X Parish in Granger and is also active at St. Augustine in South Bend.

The sacrament of reconciliation, for example, allows people to apologize and repent for wrongs they have committed, Summers said. Pastoral councils, synods and similar gatherings allow church members to voice different opinions, respect other viewpoints and come to agreement. “We should be leading the charge on how do we help the world heal and how do we help the community heal,” he said.

At the same time, people of all backgrounds need to become more aware of their biases, said Summers, who worked for 40 years in corporate marketing before starting a consulting business whose services include diversity training. “I think you have to be more sensitive to when you are treating people as ‘other,’” Summers said. “Ninety-nine percent of the time, I think it is by accident.”

Likewise, he noted, “I know in my DNA one of my biggest biases is I expect to be treated as ‘other.’ So I need to stop and think, ‘Did what I hear really mean that, or is it my mind spinning it another way?’”

Broader perspective

The Church also could benefit from thinking more broadly about vocations, said Father David Jones, pastor of St. Benedict the African Parish in the Archdiocese of Chicago. The parish was founded to serve African American Catholics but now includes African immigrants and people of African descent from South America, Father Jones said.

Even with its much larger Black Catholic population, the Archdiocese of Chicago has ordained an African American priest about once every 12 years, he said. However, the response of his parishioners during the coronavirus pandemic led him to think about vocations in a new way.

Parish members really pulled together early on to make sure they and others stayed safe, Father Jones said. People formed strong personal connections through online programming that the parish offered while they couldn’t meet in person. The online approach made it easier to stay in contact with young people, who then began asking to get actively involved in ministries at the parish.

The individual and Church both benefit as people pursue vocations of ministry within the parish, Father Jones said. That experience eventually could lead some people to consider becoming a priest or joining a religious order, he added, but that shouldn’t be an all-or-nothing goal.

“Catholics must develop a culture of vocations — in our homes, parishes and schools,” Deacon Tardy said. “Someone local must champion vocations. Conversations about marriage, religious or clerical vocations must become as normal as those about going to college or joining the military.

“Parishes and schools should have vocations committees to create awareness of diverse vocation stories, to more regularly foster discernment (for example, vocation days and projects) and to identify resources for further discernment and support,” he said.

“Most importantly,” he added, “folks need ready access to the steps to take if contemplating a religious or clerical vocation.” He recommends four: spending time in prayer to determine one’s vocation; learning through service whether one is called to obediently serve others; speaking with a pastor, religious sister, youth minister or deacon and acting on possible vocations by meeting with those who help in vocation discernment.

We all have the power within us to get where God wants us to go, Deacon Tardy said.

“If you look at the resources of the Church,” he added, “I think we have the tools to get there together.”

In service and example of vocation to the Lord

Deacon candidate James Summers

James Summers has always treasured his Catholic faith, but it took decades for him to consider stepping beyond the role of a layperson.

Summers, 70, grew up a cradle Catholic in Evanston, Illinois, a member of a family whose maternal roots in the Catholic faith go back seven generations. His mother’s father was a pharmacist, and he and his wife moved their family to Evanston in the early 1900s.

Summers met his future wife, Wendy, while they both were in college. Her Catholic roots stretch back 10 generations, so they had a strong connection. He and Wendy, who now have been married for 46 years, first lived in the Oak Park area in Chicago.

“I’ve been a lector ever since we got married,” James said. “Her dad was a lector, and I really respected him.”

A job offer he received from Whirlpool Corporation brought them to Granger, near South Bend, in 1999. There they became active members at St. Pius X Parish.

Over the years, Wendy and other people occasionally suggested James consider becoming a deacon. He always dismissed the idea, as he couldn’t see himself in that role at that time.

He started to roll back his defenses after he and Wendy attended a National Black Catholic Congress meeting in 2012 in Indianapolis. He was inspired by seeing so many Catholics that look like him and who were so joyful in celebrating the Mass.

“I had never felt so included in the Church as with that experience,” he said.

He soon joined the National Association of Black Catholic Administrators. One of the association’s priorities was sharing the good news of the gospel with more African Americans.

At one of the association’s national meetings, he told some people he was thinking of entering training to become a deacon. The outpouring of support he received encouraged him.

He also was involved as a volunteer with SCORE, a nationwide mentorship program designed to aid people in starting small businesses, where he mentored mostly women and people from minority communities. “In all reality, though, my real contribution is to provide hope in the face of discouragement,” he said.

The work sometimes left him frustrated or disheartened, and he wondered why he kept going back to it. A friend suggested he read the book, “Falling Upward,” by Franciscan priest Father Richard Rohr.

Father Rohr describes the first stage of life as a time of filling the “container” to build a livelihood, support a family and other essential responsibilities, Summers said. Father Rohr sees the second half of life as a time of emptying the container by giving back.

James read the book just before the current class of deacon candidates began their formation in January 2020. About that time, Wendy also asked him again if he wanted to pursue a vocation as a deacon. He said yes.

He asked God to let him know if the Lord really wanted him to enter formation. James thought he would be too old to participate. His answer came when Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades waived the age limit.

James is now entering his fourth and final year of formation. He would become the diocese’s second African American deacon if ordained in 2023, joining Deacon Mel Tardy of St. Augustine Parish in South Bend.

“I have learned so much about my Church in the last three years, it is mind-blowing,” James said.

One of the greatest gifts of formation training, he said, has been going deeper in prayer. Deacon candidates observe the Liturgy of the Hours, including morning prayer and evening prayer. They have become his favorite times of the day — praying and then sitting in the presence of God.

Brother Roy Smith

Sister Demetria Smith

Brother Roy Smith and one of his sisters, Sister Demetria Smith, each heard God’s call in their youth. They responded after people around them invited and encouraged them to consider a religious vocation.

The Smiths grew up as part of a large African American Catholic family in Indianapolis. Their father had converted to Catholicism while working for the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul religious order in Indianapolis, said Sister Demetria, MSOLA. She is a member of the Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Africa. Their mother joined the Church after their parents decided to marry.

Sister Demetria, 89, said she had wanted to go to Africa since seeing a photo of two boys standing on the equator in Africa in one of her textbooks in fourth or fifth grade. As a youth, she also accompanied some Daughters of Charity sisters who went out to care for the poor and felt a strong pull toward that work.

Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Africa members stopped in Indianapolis periodically on recruiting trips, including at the Daughters of Charity’s St. Vincent Hospital, where the future Sister Demetria worked as an aide. Her father told the sisters of his daughter’s interest in Africa. They called her each time they came to Indianapolis. She eventually went with them to explore a possible vocation and never turned back, joining the order in 1952.

Brother Roy, 78, CSC, of the Congregation of Holy Cross Midwest Province in South Bend, recalls his family being actively involved in their parish. He was an altar server, and the priest often asked the altar servers if they had interest in a religious vocation.

While attending Cathedral High School, where he was a star athlete, he also began to think about working in some form of ministry, he said. The school was staffed by Holy Cross brothers, and the vocation coordinator asked him if he had considered a calling as a religious brother.

By senior year, he had decided to put a college football scholarship on hold so he could “try out” the Holy Cross brothers. He soon joined their team.

Both Smiths have led very active lives in ministry to the Church.

Sister Demetria, who now is retired and lives in Indianapolis, served for about 20 years in Africa, including in Uganda during the turbulent years of Idi Amin’s rule during the 1970s. Brother Roy, who currently is development director for the Holy Cross brothers’ Midwest Province in South Bend, has worked as a teacher and social worker at a variety of locations in the Midwest. His ministry also includes working from 1985 to 1997 at the Catholic Charities South Bend-Elkhart office, where he served as office director his last four years. He remains active at St. Augustine Parish in South Bend and has served as leader of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus and is a member of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend’s Black Catholic Advisory Board.

Brother Roy, who believes he is the only African American religious brother in the diocese, said he didn’t encounter any obstacles to pursuing his vocation. Sister Demetria did, beginning with many members of her religious order who did not understanding that her education level and culture differed significantly from that of the people the sisters ministered to in Africa.

Jesus said, “My grace is sufficient for you,” she recalled, and she sought strength in those words when facing tough times.

“As the saying goes, if God brings you to it, he will see you through it,” she added.

Both Smiths have enjoyed their vocations. “I feel I am touching people’s lives in a very positive way,” Brother Roy said. “You feel you are an instrument of the Lord’s peace.”

Deacon Mel Tardy

Sometimes finding the path to a vocation takes time and perseverance.

While growing up in the strong African American Catholic community in New Orleans, Deacon Mel Tardy, now 57, of South Bend remembers being interested in possibly becoming a religious brother but not knowing how to go about it. He also thought of becoming a priest, but the only priests he saw were white, so he wasn’t sure African Americans could become one.

The road back to his early thoughts about a religious vocation began with a family trip to Atlanta in the early 2000s. While there, they decided to attend a large gathering of African American Catholic clergy and lay people.

After speaking with one man wearing a clerical collar, Deacon Tardy remembers saying, “Thank you, Father,” thinking he was talking with a priest. “I’m not a father,” the man replied. “I’m a deacon.”

When the family returned to South Bend, he asked about becoming a deacon and was told the diocese didn’t offer a deacon formation program. He turned to God, saying that if he was supposed to become a deacon, the Lord would have to provide a formation program.

“Five years later, my pastor came up and said, ‘The diocese created a deacon program, and I put your name in,’” Deacon Tardy recalled. He was ordained a deacon in May 2011 and assigned to serve at St. Augustine.

Deacon Tardy, who is the only ordained African-American clergy member in the diocese, has gone on to hold numerous leadership positions. These include serving as current chairman of the diocese’s Black Catholic Advisory Board, president of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus and a board member of the National Black Catholic Congress. He also is an associate advising professor at Notre Dame.

St. Augustine Parish remains a key part of his ministry, however, as he and his wife Annie nurture the faith in the multicultural community that inspired him.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.