December 10, 2017 // Special

The day a mother’s love changed the world

New book brings together the mysteries, history-altering influences of Our Lady of Guadalupe

Resentment. Distrust. Violence. As the Aztec Indians came under the rule of Spanish conquistadors in the early 16th century, such was the climate of central Mexico. Deeply unsettling to the indigenous culture was the additional humiliation of their religion and way of governing, which were overturned by the foreigners. A tenuous relationship between the two had been formed by circumstance, but it barely served to suture the fresh wound.

It was in the midst of this unfriendly, even deadly climate that the Virgin Mary chose to make herself known and to claim, through her maternal love, an emerging society for the kingdom of her Son.

Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared and spoke to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, a peasant, in 1529 on Tepeyac Hill, near current-day Mexico City. Her introduction — “Am I not here, I who am your mother?” — and her message, conveyed to Juan Diego and then to the local Catholic bishop, sparked the conversion to Christianity of what would become a populous, mixed-race nation.

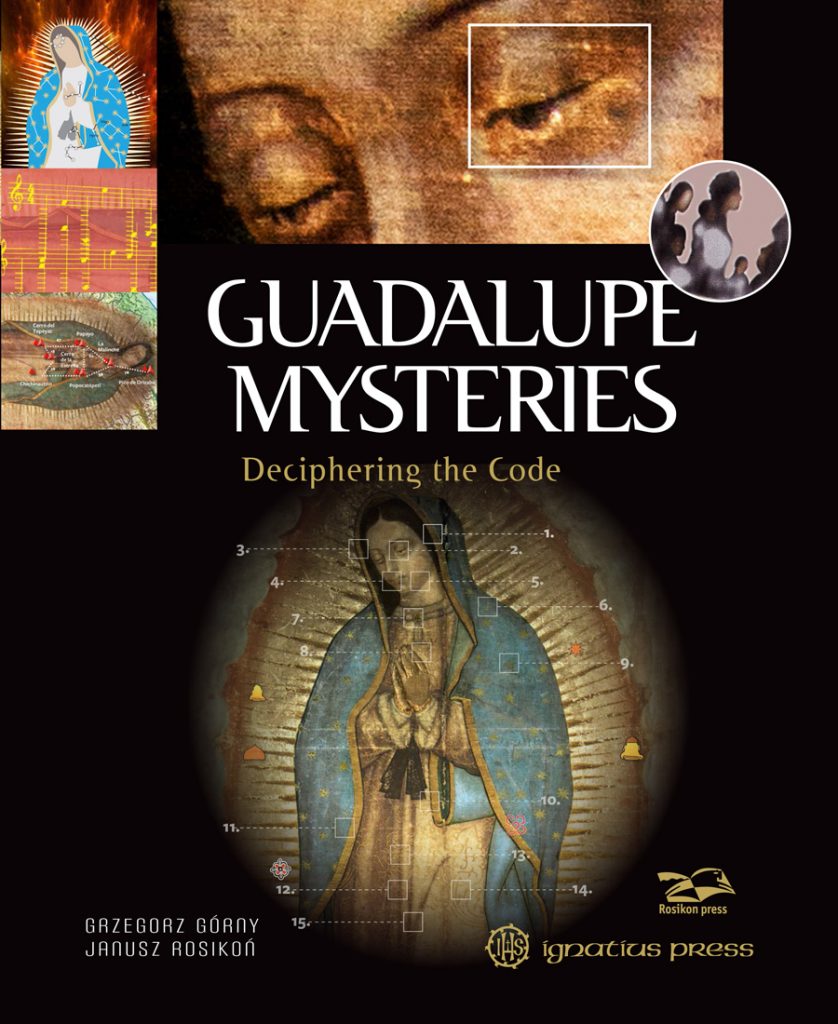

For those familiar with the miraculous, three-part Tepeyac apparition, the quantity of updated details presented in a new book, “Guadalupe Mysteries: Deciphering the Code,” has the power to revive active devotion. Those who haven’t heard the stories are likely to be not only fascinated, but moved to reflection by any number of historical accounts, testimonies and examinations presented in the engaging and well-documented work.

“Guadalupe Mysteries” reviews the apparition story and adds extensive examples of the historical context that makes the timing of her apparition sociologically relevant. Authors Grzegorz Gorny and Janusz Rosikon also present many of the scientific studies that have been applied to or performed on the cloak, or “tilma” on which her image appeared. Notably, the book also devotes an entire chapter to elaborating on how Our Lady of Guadalupe’s introduction of herself as the mother of all mankind went far beyond documenting the political and cultural path on which she set those who would come to call themselves “Mexicans,” and acknowledges her function as the lynchpin for the creation of a Catholic nation wrought from the antithesis of polytheists who practiced human sacrifice — as well as the newcomers to their land.

In addition to requisite images of the modern-day Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City — including the miraculously undisintegrated tilma, Cerrito Chapel and an iconic statue of Juan Bernadino, Juan Diego’s uncle, who was cured of a fatal illness during the apparitions and through her intercession — Gorny and Rosikon also take care to prioritize and weave throughout their book the message of salvation through Jesus Christ infused into every aspect of the apparition. Their care extends to various details of her image, whose significance was lost neither on the Indians of early colonial Mexico or the scientists, historians and faithful of today.

“The Spanish saw the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe as a Christian icon, where they found symbols that they knew well,” the authors say. Among these attributes were the blue color of her mantle, which would have been associated with “immortality and eternal happiness with God in heaven;” a sash worn about her waist, historically a symbol of virginity, purity and devotion to God; and the stars on her mantle, a reminder of her title as Queen of Heaven. These and other symbols were common iconographic elements across Europe at the time. Gorny and Rosikon then revisit the same symbols from the point of view of the subjugated Aztecs, who found familiar symbolism in the same portions of the image — making it not only intelligible, but acceptable, in a faith context to both cultures.

Over the years, scholars have analyzed the tilma’s image through a quantity of lenses that surpasses even the expected. The authors present several of these, including its geometry, the musicality of the arrangement of stars depicted on her mantle, and perhaps most intriguingly, the reflection discovered in her downcast eyes, which has been determined to consist of what appeared before her as Juan Diego let down his rose-filled tilma, as directed, in the presence of Bishop Zumarraga.

The image and inspiration of Our Lady of Guadalupe played a dominant role in the identity and tumultuous path to nationhood of the Mexican nation over the next several hundred years, as documented in “Guadalupe Mysteries.” Eventually her message of faith and divine presence filtered beyond national borders, and in 1999, Pope John Paul II confirmed its farther-reaching intention by declaring her not just the patron saint of Mexico, but of all the Americas.

While an index would have been a welcome addition, readers of “Guadalupe Mysteries” who already have familiarity with the apparition, as well as those who are unfamiliar with it, will both be served well by the book. For the former, the sheer quantity of studies and breadth of historical details presented are likely to present previously unfamiliar material or details. For the latter, Gorny and Rosikon structure the book in an easy-to-read, easy-to-pick-up-and-put-down manner that includes plenty of powerful yet easy-to-understand diagrams, historical photos, paintings and photographs.

“Guadalupe Mysteries: Deciphering the Code” provides a complete picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe’s historical influence and a reminder of the constant, conscientious care bestowed on us by our Lord and the woman who is both His, and our, mother.

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.