December 10, 2020 // Diocese

Christmas tradition lives on for Eastern European descendants

Bread has great significance in a Catholic household. Jesus called himself the “Bread of Life.” He was born in a town named after the dietary staple. (Bethlehem meaning “house of bread.”)

Catholics break bread at Mass, but some Catholics break bread on Christmas Eve. The traditional Polish meal called “wigilia,” which is eaten late on Christmas Eve, involves sharing the “opłatki,” a custom carried on by many families in the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend.

An “opłatek” wafer — opłatki is the plural form, in the Polish language — is roughly index card-sized, made of only flour and water and similar to a communion wafer. They are typically embossed with a Christmas scene such as the Nativity. Opłatki usually come four in a package: three white and one pink. In olden days the pink one was meant for the household animals, though this is not always followed in modern times, particularly for city-dwelling families who do not own livestock. According to the Polish Women’s Alliance of America, one who is pure of spirit is able to hear animals who have consumed the opłatki speak at midnight.

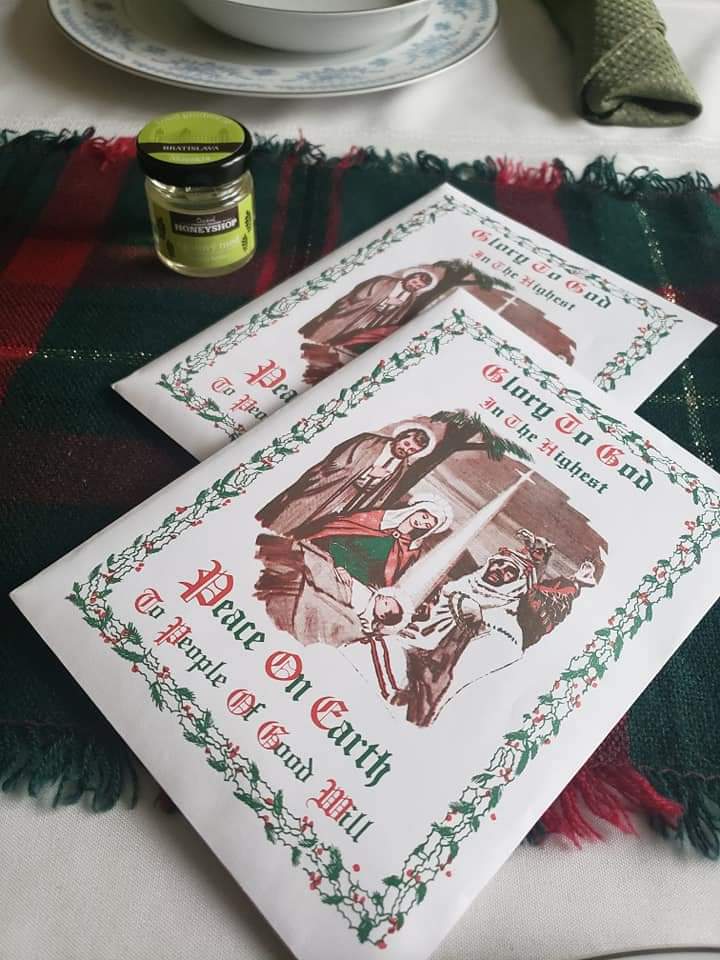

Photos provided by Kathy Fech

“Opłatki” bread wafers are part of a traditional Eastern European Christmas Eve celebration, symbolizing the eucharistic feast and offering loved ones well wishes for the upcoming year. The practice is widespread in Polish, Slovak and Lithuanian countries, and the style of the meal varies little among these ethnic groups.

Several parishes in the South Bend area were founded by Polish immigrants, including St. Hedwig, St. Casimir and St. Adalbert.

Mary Ann Sommers is a lifelong member of St. Casimir. Both sides of her family boast Polish ancestry, and her memories of the Christmas tradition go back “as far as I can remember,” she said.

On Christmas Eve in Polish households, the family gathers for the wigilia, in which the table is set with a white cloth and a place setting is left for the Christ Child. Sommers has been told that her “busia,” or “grandmother,” used to put hay underneath the table for the animals present at the Nativity, though Sommers has no memory of this.

At the beginning of the meal, the family breaks and shares the opłakti. She described the tradition as wishing others around the table well for the coming year; that they “always have food throughout the year.”

“We share the holy wafers. Through this sharing we are God bound to forgive each other all the wrongs, real and imagined, which have been committed through the year … and promise never to return to them. Only then do we have a valid sharing of the holy wafers. As Christ forgives us, so we forgive each other. Then Bethlehem, the House of Bread, where the True Bread from heaven was born, is born from above, among us, in us. For this reason the Christmas wafer is called the “Bread of Unifying Love.”

— from the back of Oplatki packages

Sommers believes that while some other Polish traditions may be limited in practice among those of the ancestry, sharing the opłatki is fairly universal and practiced throughout the U.S. St. Casimir and St. Adalbert parishes announce when the wafers are available to purchase and they sell out every year. When people travel to relatives’ homes for the holidays, they take the tradition with them.

Her own two children are grown and she expects they will continue to carry on the custom. Her son particularly enjoys it and eats any of the leftover pieces of opłatki.

There are certain prayers to be said with the breaking of the opłatki, sometimes in the native Polish. Since Sommers’ grandmother died when she was young, the spoken prayers are now forgotten — though the tradition lives on. “I wish I knew more of the language. … I kind of get the gist when people speak it.”

Those of Polish ancestry are not the only ones who maintain the tradition. It is popular in Lithuania, Latvia and Slovakia as well. Dennis Fech, a member of St. Vincent de Paul Parish in Fort Wayne, traces his ancestry back to the Carpatho-Rusyn peoples, a minority population near the Carpathian Mountains of Slovakia where he still has distant relatives. He was born into the Byzantine Rite, though his father changed from Eastern Rite Catholicism to the Roman Rite.

“I wish you much happiness, and good fortune, and after this life an eternal crown in heaven.”

— traditional Oplatki Christmas Blessing

For the Feches, Slovak culture has been a part of family life, including the tradition of breaking “opłatky ,” as it is spelled in Slovak, on Christmas Eve. In Slovak the meal is called “vilija” or “stedry vecer.” In Lithuanian, it is known as “kucios.”

He explained the custom in his own family. “Going back, there’s a whole traditional menu that is served on Christmas Eve and that’s kind of what we try and follow. We don’t do everything that I had growing up, partially because the new generations don’t care for much of what we had traditionally.”

The meal is typically meatless, as a part of the long-lost tradition of fasting during Advent. Reading from a Slovak cookbook from a previous parish, he pointed to many of the foods that are still part of the Fech family meal, such as “bobalki,” a sweet bread soaked in milk, and poppy seeds, mushroom soup and smoked fish. Stewed prunes are no longer on the menu.

His children and grandchildren still look forward to the meal. “It’s just something to hold on and grasp and have a humble meal … It’s in preparation for the coming of our Lord. That’s really what we’re preparing for.”

In common practice, the wigilia table is set with a blessed candle at the center to symbolize the Star of Bethlehem and Christ as the Light of the world. The Fech family candle has the Eastern cross engraved on it. The meal is supposed to take place after the first star appears in the night sky and is often followed up by singing Christmas carols until midnight Mass.

Before the meal comes the opłatki. Each member of the family is given a wafer, “but we break it and pass a piece to the person sitting next to us. And then it’s served with honey,” he said.

Fech is certain his is not the only family in Fort Wayne that practices the oplatki tradition, because many participate in other Eastern European traditions in the Catholic community.

As people continue to relocate from state to state or city to city, they bring their family’s culture with them. Father Timothy Wrozek, pastor of Immaculate Conception in Auburn, is of Polish ancestry and has worked to keep this tradition alive in the parishes he has served. “I used to give opłatek wafers to people when I was down in Wabash and at St. Charles.”

His memories of Christmas Eve include a white cloth in the center of the table covered with straw and opłatki sitting atop the straw. He explained that custom is very eucharistic; that it symbolizes the breaking of the bread and sharing it with others, even strangers, if any are present at the meal.

In his own family, he expects the tradition will die out simply because family members cannot find the wafers locally. He bought them from Detroit and said that sometimes family members and friends send opłatek to each other, similar to the sending of Christmas cards.

Father Wrozek told of how he used to buy the wafers in boxes of 100, put them in envelopes with the instructions for the associated ritual, and distribute them to people at St. Charles Borromeo Parish in Fort Wayne when he was associate pastor there. Those who received them would give a small donation, though he never charged for the wafers. “Fifty or sixty people of Polish descent heard I did that,” he commented. “I always ran out.”

The best news. Delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe to our mailing list today.